Table of Contents:

Milkweed 101

There’s something creeping its way through our American landscape, a quiet, unassuming thing. Maybe you have seen them along the sides of roadways, in open fields, or in someone’s front garden. It seems more and more to be a force that cannot be stopped. Has milkweed hypnotized the nation, or is this plant craze justified?

There’s been a lot of talk about milkweeds recently, especially in regards to their relationship with the regal monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus). An entire movement has sprung up around monarch waystations and butterfly gardens- a dispersed effort to bolster the population of a migratory lepidopteran- with milkweeds sitting directly in the center. Personally, I find it wonderful that these common, often weedy, plants are finally getting the attention they rightly deserve. If you already know what milkweeds are, feel free to skip down to the next section.

Milkweeds are a rather large subfamily of plants, Asclepiadoideae, comprising roughly 2,900 species under the larger family, Apocynaceae, and are on every continent except Antarctica. That subfamily contains 348 genera, all of which could be called “milkweeds,” but what we typically consider a milkweed belong to the genus Asclepias, which we can then narrow down to roughly 200 species; Ohio claims 13 species within its arbitrary boundaries. Those species are:

- A. amplexicaulis

- A. exaltata

- A. hirtella

- A. incarnata

- A. purpurascens

- A. quadrifolia

- A. sullivantii

- A. syriaca

- A. tuberosa

- A. variegata

- A. verticillata

- A. viridiflora

- A. viridis

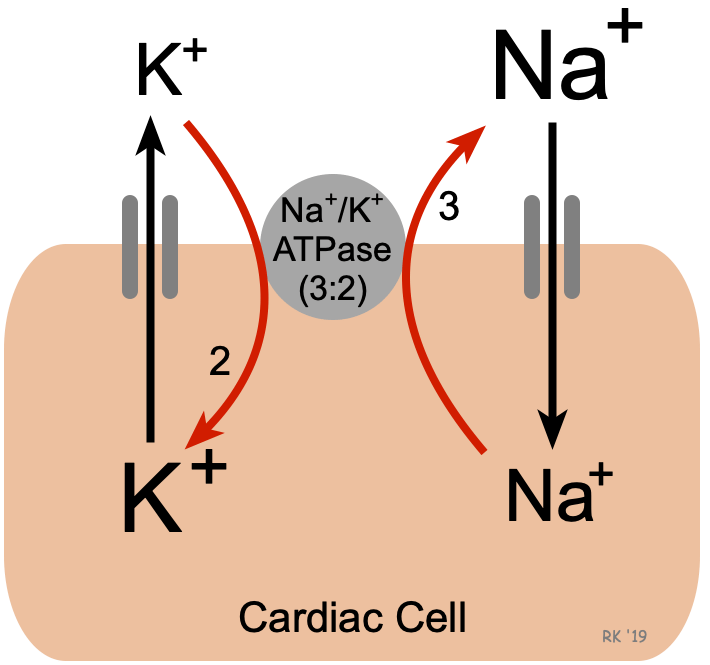

Plants in Asclepias are fairly easy to identify based on features. For the most part, milkweeds are 1-5′ tall herbaceous flowering plants, with oppositely arranged, simple leaves; and showy, 5-petaled, umbellate flowers borne from the leaf axils. Two species in Ohio that break those rules are A. verticillata and A. tuberosa, whose leaves are whorled, and alternately arranged respectively. Milkweeds earned their name from the white latex that leaks out when stem or leaf tissues are damaged. The latex is filled with toxic compounds that members in Apocynaceae share; broadly, a smattering of cardenolides- a type of steroid often derived from sugars- which have the ability to stop one’s heart through inhibition of Na+/K+ channels across cell membranes. To give you an idea of how toxic Apocynaceous cardenolides are, oleander is another member of Apocynaceae, and is responsible for many poisonings across animals. Eating several leaves is enough to potentially stop your heart.

Indeed, this family is deadly; Apocynaceae is based on an ancient Greek word, apókunon, that means “dog away,” (Ἀπόκυνον, wiktionary) and was used as a dog deterrent/poison. That being said you don’t need to really worry about succumbing to its poisons, milkweed poisoning is rather rare. Thankfully, like most other botanical poisons, they are quite bitter. What you do have to worry about though is getting more invested in milkweed biology.

Small-fly bear traps

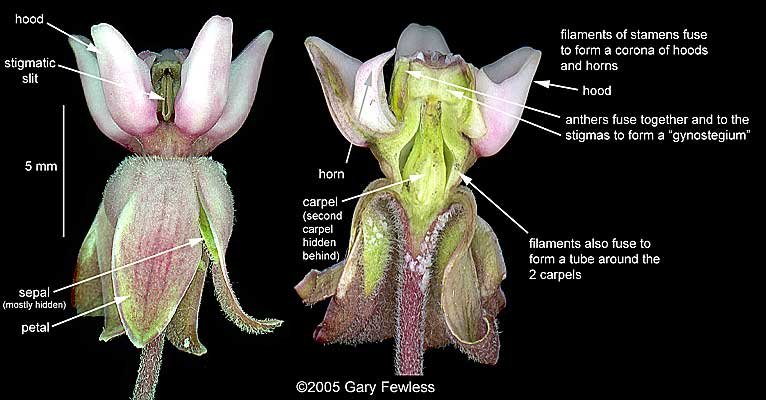

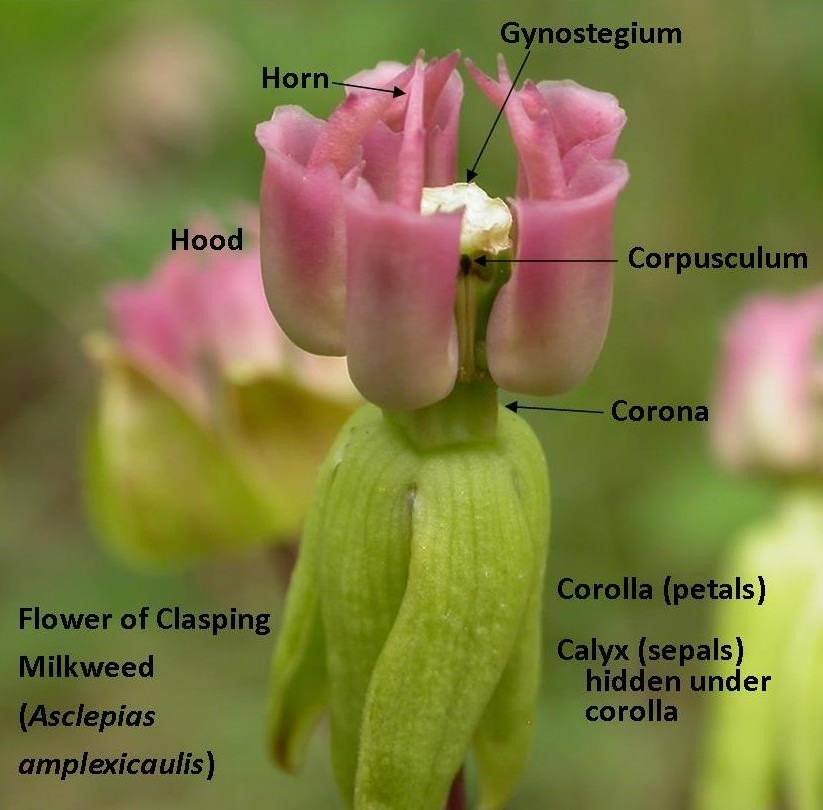

Listen, the taxonomic and chemical information on milkweeds is all well and good, but where this taxonomic group really shines is in their floral structures. They are quite possibly one of the most intriguing and intricate floral structures in the botanical world. Milkweed flowers are highly modified and look dissimilar to most other flowers thanks to a structure called a gynostegium. The gynostegium in milkweed flowers is the central column that stands out from the reflexed petals and sepals. That structure is the result of the stamens and stigma fusing into one structure. In milkweeds, the 5 anthers are presented on the sides of the gynostegium which straddle 5 stigmatic slits. Surrounding the gynostegium is what’s known as the corona which are 5 combinations of hoods and horns and are made of filaments.

Enough on form, let’s talk function. Milkweed sex is unusual but not unique. Milkweed pollen is not free floating but packaged into structures known as pollinia. Two pollinia are produced per anther and are connected by two arm like structures (known as translator arms) to a sticky black disc known as the corpusculum. This entire structure is known as a pollinarium. Through convergent evolution, only orchidaceae has adapted similar pollen-sac structures. Both systems function through attaching their pollen sacs on to insects that visit their flowers, although through different mechanisms. Milkweeds rely on large, clumsy insects, mostly bees and wasps, to walk along their flowers and slip into one of the many stigmatic slits. There the corpusculum of the pollinarium becomes attached and then comes out with the leg. Hopefully, the insect continues with its haphazard nature on a separate milkweed plant where the process repeats again, but this time the pollinarium is inserted into the stigmatic slit, pollinating the flower. Milkweed flowers develop into fruit known as follicles which split open when ripe and release hundreds of silky wind-dispersed seeds. This is like reading very sophisticated smut isn’t it?

Lab from Beltsville, Maryland, USA

That was the basic summary, but I know how you sick freaks operate; y’all want more, and I will happily oblige. Remember the corona from before and how they’re actually filaments? Well, they’re chock full of nectary goodness. In fact, the nectar is 3% sucrose (Wyatt et al, 1992)- which doesn’t sound like a lot, but if you’ve ever deeply inhaled a milkweed inflorescence you can attest it is. Those filamentous honeypots act as beacons for many insects looking for food, especially when you consider that most milkweeds produce copious flowers on globular umbels. That’s an insect buffet right there. So, if you’re a large bee walking from flower to flower on an inflorescence, your six legs are going to be slipping off of waxy horns and hoods and falling into the stigmatic slits. From before, we know this process results in a successful transfer of a pollinarium on to a leg. But, post removal is where the real magic happens; the pollinarium quickly dries out and the translator arms change shape to reorient the pollinia to be in the proper orientation to be inserted into the stigmatic slit of another flower where they will break off and pollinate the flower. That is evolutionary finesse of the grandest scale.

Despite the ballet of bee and pollinarium described above, there is a self-selecting caveat with milkweed flowers. To remove the pollinarium with your clumsy insect legs thicker legs are better, but also stronger legs are required. Here, literally, thick thighs save lives. If an insect such as a house fly or honeybee were to step into a stigmatic slit and touch the sticky corpusculum, the insect would be unable to remove its leg, like a reproductive bear trap. Some insects, like the fly, are too weak to remove the pollinarium, leaving them with two options:

- Lose the leg

- Die

I’ve seen this happen before, and over on my Instagram (@watchingplantsexinthewoods), it is one of my most popular reels. It’s quite a shocking thing to see. If I may crassly anthropomorphize for a bit, imagine you are the fly whose leg is stuck in a plant vagina with only the above options. Gruesome. Milkweed flowers: incredibly complex, unique, and terrifying if you’re a small fly.

But what about the Arthropods?

Milkweeds are fountains of life (maybe not for dogs) and are critical members of many prairie habitats where they are often found. Many species of wasps, bees, beetles, butterflies, moths, and true bugs use members of Asclepias as essential food sources throughout their life stages. When visiting milkweed plants you’re likely to see a continual cast of characters. There are multitudes of arthropods that associate themselves with milkweeds but for today we will only focus on a few.

First, an anecdote from my wildflower garden. Aphids are a garden pest that stymie many gardeners. Aphids reproduce in high numbers and their sucking mouthparts can overwhelm the plants they feed upon. I’ve witnessed many young, misshapen milkweed shoots covered in aphids. Usually, ladybugs get all the glory in decimating aphid populations, but many insects feed on aphids. This year my restored prairie patch had its common milkweeds (A. syriaca) covered in aphids and after time their population dwindled due to predatory earwigs. Earwigs are quite voracious hunters of soft bodied insects and currently, are guarding the soft growing tips from predation. Although, earwigs and aphids are not the only arthropods to make milkweeds their home.

Second, a common sight on Asclepias syriaca flowers and especially the fruit pods are the red milkweed beetle, Tetraopes tetrophthalmus. These beetles, more orange than red, are entirely associated with common milkweed and are most likely to be the insect you come across when visiting common milkweed. As larvae, T. tetrophthalmus feeds on the roots of A. syriaca and then transitions to chewing leaf, stem, bud, and fruit tissue as adults (“Red Milkweed Beetle (Family Cerambycidae).”, 15 May 2017). As previously discussed, milkweeds contain toxic cardenolides within their tissues that are deadly toxic to most animals. Through altered ATPase pathways, insects that feed on milkweed can consume without risk of mortal peril, but there’s another issue these herbivores have to overcome: the latex. When milkweed tissues are damaged, latex flows from the sapstream which deters herbivory through its toxic compounds, sealing the wound, and also gluing the mouthparts shut. T. tetrophthalmus overcomes this hurdle by severing leaf veins above the point where they will be feeding (“Red Milkweed Beetle (Family Cerambycidae).”, 15 May 2017). The severing reduces sap-stream pressure and allows the beetle to eat leaf tissue without becoming overwhelmed with latex. If their mouthparts do become coated in latex, the beetles usually clean it off quickly before it can harden and get back to feasting (“Red Milkweed Beetle (Family Cerambycidae).”, 15 May 2017). Feeding by T. tetrophthalmus on common milkweed doesn’t exist in a vacuum of course, it affects the milkweed it feeds upon and other potential herbivores.

A 2014 study looked into the effects of above-ground and below-ground feeding by T. tetrophthalmus and found several important details. Foremost, early-season, above-ground feeding by adults increased the survivability of root-feeding larvae later in the season, but not vis a versa (Erwin et. al., 2014). In addition, this early-season feeding served as an attractant to another leaf-chewing herbivore, Labidomera clivicollis, who together reduced fruit production by a third (Erwin et. al., 2014). Interestingly, this study highlighted a behavior in monarch butterflies that had been observed before. Prior leaf chewing by T. tetrophthalmus and Labidomera clivicollis reduced egg laying by monarchs, who eschew previously munched on milkweed; apparently, previously predated milkweeds can reduce the growth of larvae that feed upon the same plant (Erwin et. al., 2014).

Finally, we come full circle to discuss monarchs and milkweeds. Other than their ecological overlap with the red milkweed beetle, the migratory monarch has a whole suite of milkweed interactions. Monarchs migrate across N. America in multigenerational groups to Mexico and California in the winter, and across southern Canada and the continental United States in spring and summer.

During their migrations, adult monarchs feed upon many species, not just milkweeds, but will only lay their eggs on milkweeds. Their caterpillars feast upon the leaves of milkweeds , bulking up on mass and concentrations of toxic cardenolides, now repurposed as anti-predation compounds. The toxic and bitter flavor of the sequestered cardenolides deter most predators, but monarchs also possess another defensive measure: warning colors. Like the previous red milkweed beetles, monarchs have bright color patterns that warn predators of their toxicity, a term biologists call ‘aposematism.’ Together, these traits allow the caterpillars to mature through adulthood. Monarch caterpillars eat a lot of milkweed leaves and as a result have to go through 5 molting events, or instars, before they are ready to pupate and return to their butterfly stage. For monarchs, not all milkweeds are the same.

There are 27 known species of milkweeds in the genera Asclepias and Cynanchum that are larval hosts for monarch butterflies spread across the continental U.S. and Mexico (Malcolm & Brower, 1989). Each species has differing concentrations of cardenolides. Migratory monarchs generally display preferential egg-laying habits towards milkweeds with moderate cardenolide content (Malcolm & Brower, 1989) with a few exceptions. Monarchs require cardenolides in high enough quantities to confer protection from predators, but not high enough to reduce larval survival; it’s for this reason that monarchs typically are observed avoiding ovipositing on A. tuberosa and A. verticillata, which have low cardenolide contents (Pocius et al, 2018). High cardenolide milkweeds are typically eschewed by monarchs because of increased mortality to larvae that consume their leaves. The exception to the case here is when monarchs leave their overwintering sites in Mexico and Californica to travel north again in spring (Malcolm & Brower, 1989). Overwintered monarchs have lower levels of cardenolides than their migratory generations; it’s hypothesized the monarchs prefer higher cardenolide milkweeds here to give the first migratory generation extra protection (Malcolm & Brower, 1989).

On the note of milkweed-induced larva lethality it should be mentioned that while monarchs are resistant to cardenolides, they aren’t impervious, and different species result in different rates of survival for monarchs into adulthood. Of nine species studied in a greenhouse setting, seven species resulted in over 50% survival. The two species with the lowest rates of survival were A. hirtella (30%) and A. sullivantii (36%), likely due to high concentrations of cardenolides; the two species with the highest rate of survival were A. tuberosa (75%) and A. exaltata (72%), likely due to low concentrations of cardenolides (Pocius et al, 2017). As it turns out for monarch mothers, milkweeds matter.

If you’re coming to the end of this and want to plant your own milkweeds to help migratory monarchs then the best advice that can be given is to find what species grow in your area and what milkweeds match your property’s habitat, and to plant multiple species- according to Pocius et al 2018 monarchs oviposit more when there are multiple species present. Planting milkweeds outside of their natural range can cause monarchs to lay eggs when they should be migrating which results in lower migrations (Satterfield et al, 2015). The Xerces Society has a great tool to help you find appropriate milkweed species. One of the worst things you can do for migratory monarchs- other than removing milkweeds- is to plant the tropical milkweed, A. curassavica.

Tropical milkweed is often sold as an ornamental milkweed, and I must admit it is quite stunning, but there are a couple of issues this plant causes for monarchs. For one, A. curassavica can bloom later than many native species and will continually grow in more mild southern states. Monarchs who encounter these plants can depart from their migratory or overwintering habit and breed instead, and in Florida this has caused a population of non-migratory monarchs to establish (Satterfield et al, 2015), (Wheeler, 2018). This effectively reduces the population of migratory monarchs, and if this wasn’t bad enough, A. curassavica carries another risk, parasites. Monarch and queen butterflies are the only hosts for the protozoan parasite, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, or OE for short. OE can be found on any plant that these two species visit, but A. curassavica carries OE at higher rates than normal thanks to its year-round growth habit (Satterfield et al, 2015) (Wheeler, 2018). The OE parasite is deposited on to plants by adult butterflies and their offspring pick it up as caterpillars when they eat the leaves. When infected by OE, monarchs and queens have developmental issues following pupation which result in misshapen wings, lower body mass, limited flight ability, and shorter lifespan (Satterfield et al, 2015) (Wheeler, 2018). Tropical milkweed is increasing the population of OE and increasing the likelihood of high OE infection in migratory monarchs. For healthier monarch populations, please, kill this plant today. Would it kill ya to do a little plant terrorism, huh?

And hey, thanks for reading. Now go spend the rest of your day wondering what it would be like to have 15 appropriately scaled pollinariums attached to your legs for hours at a time.

Citations

- “Ἀπόκυνον.” Wiktionary, en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%E1%BC%80%CF%80%CF%8C%CE%BA%CF%85%CE%BD%CE%BF%CE%BD#Ancient_Greek. Accessed 23 July 2023.

- Erwin, Alexis C., et al. “Above-Ground Herbivory by Red Milkweed Beetles Facilitates above- and below-Ground Conspecific Insects and Reduces Fruit Production in Common Milkweed.” Journal of Ecology, vol. 102, no. 4, 2014, pp. 1038–1047, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12248.

- Malcolm, S. B., and L. P. Brower. “Evolutionary and Ecological Implications of Cardenolide Sequestration in the Monarch Butterfly.” Experientia, vol. 45, no. 3, 1989, pp. 284–295, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01951814.

- Namestnik, Scott. “Milkweed Flower Morphology and Terminology.” Orbis Environmental Consulting, Feb. 2014, orbisec.com/milkweed-flower-morphology-and-terminology/.

- Pocius, Victoria M., Diane M. Debinski, John M. Pleasants, Keith G. Bidne, and Richard L. Hellmich. “Monarch Butterflies Do Not Place All of Their Eggs in One Basket: Oviposition on Nine Midwestern Milkweed Species.” Ecosphere, vol. 9, no. 1, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2064.

- Pocius, V M, et al. “Milkweed Matters: Monarch Butterfly (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) Survival and Development on Nine Midwestern Milkweed Species.” Environmental Entomology, vol. 46, no. 5, 2017, pp. 1098–1105, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvx137.

- “Red Milkweed Beetle (Family Cerambycidae).” Field Station, 15 May 2017, uwm.edu/field-station/red-milkweed-beetle/#:~:text=They%20dwell%20in%20the%20soil,briefly%20in%20spring%20before%20pupating.

- Satterfield, Dara A., et al. “Loss of Migratory Behaviour Increases Infection Risk for a Butterfly Host.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 282, no. 1801, 2015, p. 20141734, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.1734.

- USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab. “File:Melissodes Trinodus, f, Foot, Polynia of Milkweek, AA Co, MD 2014 …” Wikimedia Commons, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Melissodes_trinodus,_f,_foot,_polynia_of_milkweek,_aa_co,_md_2014-07-09-19.33.21_ZS_PMax_(14436615847).jpg. Accessed 24 July 2023.

- Wheeler, Justin. “Tropical Milkweed-a No-Grow.” Xerces Society, 19 Apr. 2018, xerces.org/blog/tropical-milkweed-a-no-grow.

- Wyatt, Robert, et al. “Environmental Influences on Nectar Production in Milkweeds (Asclepias Syriaca and A. Exaltata).” American Journal of Botany, vol. 79, no. 6, 1992, pp. 636–642, https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1992.tb14605.x.

Leave a reply to Laird Haynes Cancel reply