Ohio is dominated by temperate forests with remnant wetlands, prairies, and savannas scattered throughout.

Ohio is predominated by sedimentary rocks, with many regions containing high amounts of limestone bedrock- a testament to the history that this region used to be a sea many million years ago. Check out Ohio’s interactive geology map here.

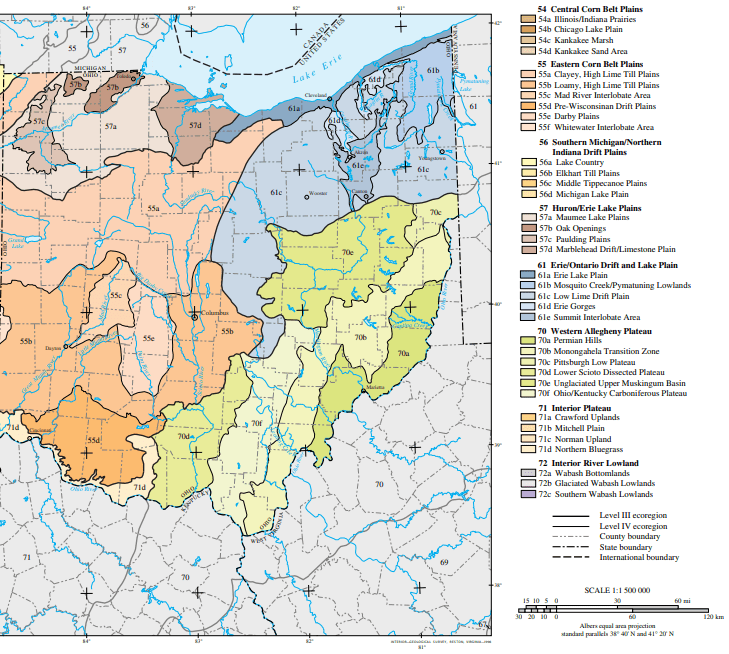

Also informing the geological history in Ohio is the periods of glaciation that carved the landscape into its current shape, flattening many regions and forming large valleys in others; the only region to be spared in Ohio from glaciation is the Western Allegheny Plateau. Glacier melt also left us with several wetland systems like the kettle bogs in NE Ohio.

Finally, Ohio is a fairly moist state with an average annual rainfall of about 30-50 inches (depending on year and region). The lack of surrounding mountains and the presence of Lake Erie means Ohio receives arctic blasts of cold and humidity in the winter and plunges of humidity and storms coming up from the gulf and Atlantic Ocean.

All of these factors have shaped the flora in Ohio.

North East Ohio

North East Ohio is closest Ohio comes to a Mediterranean climate. This may sound weird if you have never botanized in some of the valleys around Chagrin Falls or Chardon, or the swamps & bogs in Rock Creek or Newbury, but the humidity and abundance of groundwater helps this region specialize in plants that love humidity and wet soils.

Lake Erie pumps moisture into this region throughout the year, giving this region some of the highest annual rainfall of all Ohio; in fact the Morgan Swamp in Rock Creek exists because of a yearly dumping of snow. In addition, Lake Erie provides a climatic buffering effect, keeping the immediate region on average warmer in the winter and cooler in the summer than the surrounding locales.

Headland Dunes

The shores along Lake Erie used to contain several sand dunes. Unfortunately, all but one have been destroyed. This habitat is unlike anything else in Ohio. The sand dunes still receive a lot of tourists and beachgoers, but the conservationists in charge are doing a fine job protecting the plants on the fragile dunes and the threatened birds that call this place home.

Grand River

One of the major rivers in NEO, the Grand River supplies water to many forests and wetlands and also boasts an impressive diversity of flora and fauna, and is also the home to several threatened plant species. This river dumps into Lake Erie at Fairport Harbor, OH (my former home) and sources its headwaters in SE Geauga county. It is here that most feels like a temperate tropical rainforest (especially in in Hidden Valley); copious waterfalls, nutrient-rich floodplains, and misty rains makes the hemlocks grow huge here and the surrounding flora copious. Hydrastis canadensis, Lilium superbum, and Castanea dentata can be found here.

Morgan Swamp

Morgan swamp is a relict of a much larger wetland complex, but now this preserve is a shadow of its former self, but none the less impressive to see. Eastern Hemlocks, Yellow Birch, Oaks, and Maples make up the majority of the canopy here. Thanks to the high amount of winter snowfall and regional cooling, this swamp has been able to survive. Many rare and threatened flora and fauna make their home here, most notably, Trillium undulatum and Neottia cordata.

Kingsville Sand Barrens

The Kingsville Sand Barrens is a relict from a much older time in Ohio. Much like the Headlands Dunes, the Kingsville Sand Barrens is a part of the former sea that covered Ohio, but now an fossil dune ridge. The soil is mostly sand with some organic materials, and thanks to the plentiful rainfall broad groups of plant species can survive here. Rare species in Ohio such as, Lupinus perrenis, Rhododendron calendulaceum, and Acer pensylvanicum all make this place their home.

Cuyahoga Valley National Park

The only National Park in Ohio, CVNP is an oddity amongst National Parks. There are highways running through it, golf courses, and small towns. This feels less like wilderness, and more like a giant metro park. Alternatively, the largest waterfall in Ohio (the Brandywine) and a stunning exposure of Sharon Pebble Conglomerate boulders dropped from glaciers, call CVNP home. That being said, there are lovely plant communities here that are absent elsewhere in this region.

Burton Wetlands

The SE-central region of NEO contains a preponderance of interconnected wetlands. Burton wetlands is a fantastic little kettle bog- a type of wetland that resulted from previous glaciation- that houses many species that are difficult to see elsewhere.

Triangle Lake Bog

Another kettle bog a bit south from Burton Wetlands. This bog contains more species that you normally think of being in acidic bog plant communities. This bog is one of the few remnant populations of Sarracenia purpurea & Drosera rotundifolia.

North Central, North West Ohio

As one travels westward of Cleveland, precipitation lowers and the landscape transitions away from the beech-hemlock forests and deep valleys common in the eastern portion. The region flattens and remnants of the once widespread prairies and Great Black Swamp can still be seen in pockets. In addition, inland sand barrens and dunes can be found sporadically dotted in between the rare oak savannah habitats. Finally, of note, a large limestone quarry hosts a diversity of rare species along a Lake Erie peninsula. Overall, this region hosts a broad diversity of habitats from birder paradise wetlands to dry sand dunes.

Castalia

This region of Ohio has several open prairie and sand barren habitats. These types of habitats have been greatly altered and destroyed by human expansion and conversion into farmland. To visit this area is to get a glimpse into the massive pre-colonial prairieland that used to spread westward from here. This region also holds the largest (only?) population of the imperiled (S2) Cypripedium candidum in Ohio.

Marblehead

The Lakeside Daisy State Nature Preserve is a fantastic limestone barren plant community. The federally endangered Lakeside Daisy (Tetraneurus herbacea) has its largest natural population here in Ohio. Common prairie species like Liatris make their home here, but so do aggressive disturbance-regime plants like Juniperus occidentalis which can degrade Tetraneuris herbacea habitat.

Oak Openings

Oak Openings near Toledo, OH is a fantastic plant community that is one of the rarest habitats left in the US, an Oak Savannah. Black Oak (Quercus velutina) and other oak species form much of the canopy here, which is much more spread out than most of the forests that you may be used to. The groundcover is commonly ferns and graminoids with forbs mixed in. Sand dunes leftover from former glaciation and lake deposition intermix between the oak savannahs and black oak forests. The habitats here are fire-adapted and require occasional burnings to keep the canopy and understory relatively open, and to support rare species such as the imperiled (S2) Platanthera ciliaris.

********** Wet Meadow

The name of this meadow has been redacted to help preserve the habitat of the globally imperiled orchid that calls this lakeside meadow home. Platanthera leucophaea was once much greater in population but human expansion across its range has terribly reduced its population size. Unfortunately too this wet meadow has seen a loss in abundance over the years as well.

South Central, South West Ohio

The climate and habitats of the southern region of Ohio depends on whether you are in the foothills of the Appalachian mountains, or in the sandy, sprawling valleys and flatlands that head westward into Indiana. The western portion is now mostly farmland, but islands of oak-hickory & beech-maple forests and occasional wetlands can still be found. Much of the region has a bedrock of limestone, and in some areas the limestone is exposed, like in Waynesville, OH. The soil conditions also means that Juniperus occidentalis is very common across disturbed sites.

As you head eastward towards south-central Ohio, the climate becomes wetter and the valleys become closer and deeper. The only National Forest in Ohio- the Wayne- calls this region home. Much of the flora here has more in common with that of the Appalachian states than the rest of Ohio.

Waynesville

Waynesville is my hometown and also where I first seriously cut my teeth on botany in April of 2020. Most of these photos are from my first foray where myself and two others went out to look for several species, namely orchids, of which we found two. It was this trip that made me fall in love with Orchidaceae. For context, Caeser’s Creek was turned into a lake in 1978 when the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers converted it to help prevent flooding in the Miami Valley. The bedrock of the region is 450 m.y.o. limestone, from when Ohio used to be a sea, and if you head over to the spillway you can still see the ancient, fossilized seafloor. The forests surrounding Caeser’s Creek are a mixture of Oak-Hickory and Beech-Maple, and there are still a good many locations not taken over by Amur-Honeysuckle.

Cedar Bog (Fen)

Welcome to the most botanically biodiverse area left in Ohio. Cedar Bog- which is actually a misnomer, since this wetland is actually a fen but the name Cedar Bog stuck- is a remnant wetland shortly north of Dayton, OH with an incredible diversity of alkaline adapted species. The fen has a network of accessible boardwalks which lets you enjoy the incredible habitat without disturbing any of the fragile life there. This habitat feels so out of place with the surrounding agriculture and oak-hickory & beech-maple forests that surround it. There are many uncommon and rare species within Ohio that make area

Edge of Appalachia

The Edge of Appalachia (pronounced ‘app-uh-latch-uh’) Preserve is a wonderfully diverse plant community that gives you a glimpse into what Ohio used to look like before the sprawl of strip-malls and stroads took over. The foothills of the Appalachian mountains begins here and this gives you a great diversity in habitat and scenery. The landscape moves as a crumpled blanket, with rolling hills covered in a variety of habitats. Stream systems support a wealth of plant life in the hill-valleys and openings in the oak-dominant canopy reveal remnant prairie uncommon to the rest of the state. Here you can still see healthy communities of rarer Ohio plants like Cypripedium acaule, C. parviflorum, and Castilleja coccinea.

Wayne National Forest

In May 2023, my wife and I travelled to the Ironton portion of Wayne National Forest (the only NF in Ohio) as a part of a weeklong backpacking trip in search of the Whorled Pogonias (genus Isotria). Unfortunately, due to a medical emergency we could only stay a single night. Nonetheless, this region is both gorgeous and enticing. The foothills of the Appalachians deepen greatly in this unglaciated portion of Ohio and deep hollers with leisurely streams and pseudo-tropical understories reveal their glory. The holler where I briefly botanized was surrounded by sedimentary outcrops where moisture dripped off of their lips and the basin filled with an understory of dense Asimina triloba and Lindera benzoin stands. Of the few plants I was privileged to see, Synandra hispidula, a sparsely distributed mint, was the most enigmatic.

Hocking Hills

Deep gorges and towering sandstone cliffs make Hocking Hills a stunning region to visit as a tourist, and fascinating as a botanist. Glacial melt helped to bring some of the species to this region, like Tsuga canadensis, and stream erosion and tectonic uplift carved out the stunning scenery. The walls of almost every exposed rock within the gorges are covered in multitudes of lichen, moss, and fern. Stepping into Hocking Hills feels like stepping back in time. Florisitically, you can find uncommon species like Polypodium appalachianum, Valeriana pauciflora, and Oxydendrum arboreum; and the now state vulnerable (S3) Trifolium stoloniferum, if you know where to look.