A Case Study into Roadside Botany.

Table of Contents:

- A Change of Scenery

- Ohio

- Indiana & Illinois

- Missouri

- Kansas

- Colorado

- Utah

- California

- Nevada

- So Long, and Thanks For All the Fish.

A Change of Scenery

Recently, if you don’t follow me on Instagram (you should), you would know I quit my decent-paying job as an arborist in Ohio to pursue my aspirations of becoming a botanist. This involved me moving my poor self to Reno, NV- a state I’ve been to only once on a business trip- by myself making considerably less than I had before. After 5 long years of trying my damndest to get into to the professional field of botany, I’m happy for the opportunity. So, I had to pack up and drive 36 hours from my home in NE Ohio to Reno, NV. My travelling companion and I planned to save money by finding free, dispersed campsites along the way. This was partly to be save 100s of dollars, but also, we like roughing it. These 36 hrs. of drivetime and countless scenic highways gave me the perfect opportunity to see how the landscape and species distribution changes as you move westward. From this, I gained two critical pieces of info:

- I need to know more about geology and its relationship to plant communities.

- Highway roadside botany is underrated. You miss so much flying by at 80 mph.

It is my goal to explore both of these findings in this post.

My trip took me through 8 states and I observed around 190 species on INat along the way.

So, come with me again as I detail the changing floristics of my westward travels from Ohio to California! Get a grip on your smartphone-addled attention-spans, because this is the largest article I have ever written and I am not sorry.

Ohio

A brief pitstop. Cedar Bog in Urbana, OH – the most species rich region of Ohio- has become an annual pilgrimage for me since I became an amateur botanist in the upheaval that was 2020. My partner, and travelling companion, had never been to Cedar Bog so we went 20 minutes out of our way to see the magnificent orchid, Cypripedium reginae, in bloom. Thanks to the degree days, a system of measurement that ties daily temperatures to phenology, being way ahead of its usual pattern, the orchids were in full bloom a whole 2 weeks early. Unfortunately, I feel as though this is a new normal for earth.

Nonetheless, this stop felt symbolic; my Mecca was the last fen I was likely to see in a long while as I ventured more into the intermountain west. A goodbye to abundant groundwater.

After saying goodbye to my family in Dayton, OH, we were on our way to the next states.

Indiana & Illinois

Nothing to see here. Just milage on my Subaru’s speedometer.

Missouri

Our first night’s rest took us into Missouri, a state where I had been before to see the Ozark Plateaus. Two stops were made here, one, to see the historic brood XIX cicadas which are emerging at the same time as brood XII, and the other at Little Lost Creek Conservation Area to camp.

Little Lost Creek Conservation Area is a 2,899-acre oak/hickory woodland (“Little Lost Creek Conservation Area,” 2024) growing out of an Ordovician sedimentary substrate (dolomite, limestone, shale, sandstone) (Horton et. al., 2017). Intermingled with the woodlands are glades loaded with prairie-adapted species. Thanks to a pop-up rainstorm and night quickly approaching, we were unable to survey the area fully.

Two of the more exiting finds were a new (to me) species of milkweed, A. purpurascens, and a close relative to the sensitive plant, Desmanthus illinoensis, which is displaying the mimosoid-clade’s notable nyctinastic closure of their leaflets. More on the milkweeds later in Kansas.

Kansas

I grew up loving Courage the Cowardly Dog. Its surreal early 2000s art and stories shaped my humor for years to come. Famously set in Kansas, this show impressed on me how barren and desolate the Kansan landscape is. Consistently throughout my life too, many people would bemoan the arduous I-70 drive through Kansas; “It is flat nothingness,” one person would dreadfully remark, “you drive through just to leave,” another would say. The details of Kansas’ landscape seemed certain

I can say I disagree.

First off, the western Kansan landscape I will admit was nothing but flat farmland, to the testament of my influencers, but central to eastern Kansas was an entirely different story. The deep, old woods of Missouri shift into the rolling, seemingly infinite, prairies. The geology shifts to younger and younger sedimentary bedrock, with Permian soils to the east, and Cretaceous central (Horton et. al., 2017). It is of my opinion that the people who have a poor opinion of the Kansan landscape have plant-blindness, and/or hate prairie.

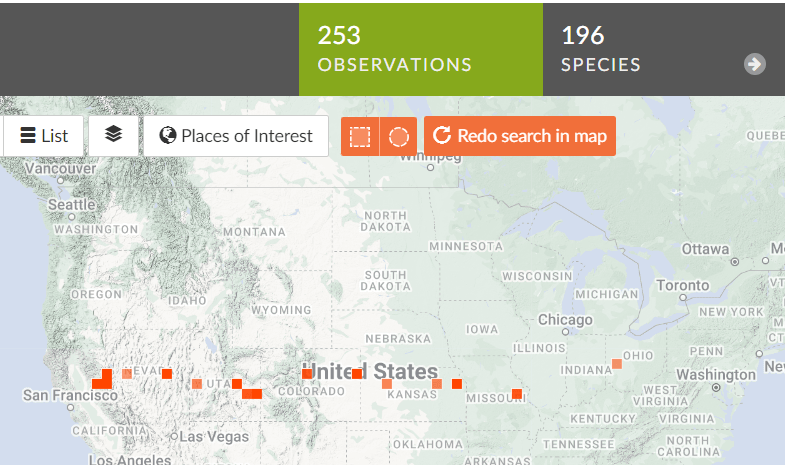

Kansas is where the roadside botany really began on this trip. Last year I spent many botanizing trips in the relictual prairies of Ohio, falling in love with their diversity and floristics. Kansas has that in spades with multitudes of tallgrass prairie adapted species. Here, in Kansas is where a floristic theme appears: the genus Oenothera. As you pass over the Mississippi river, the diversity of Oenothera broadens to encompass nearly all of the known species in the continental US.

The first stop, barely past St. Louis, was on a roadcut where tons of prairie species were in full-bloom and a panoply of invertebrates were darting from their receptive flowers.

By far my favorite find at this roadcut is the start of another westerly taxonomic motif, Penstemon. The tallest Penstemon species I have seen by far, P. tubaeflorus had a notable yeasty scent, like freshly baked sourdough. Stuck to the corollas of the Penstemon were a smattering of gnats, likely attracted by the yeasty smell. Even though yeasty (acetoin) floral scents are key indicators to gnat pollination strategies (Mochizuki, 2023), I find it unlikely they are major contributors to pollination here. Penstemon exhibits Bombus-pollination strategies, with their tubular corollas and placement of stigmas and stamens, and P. tubaeflorus is no exception. In addition, like many other Penstemon species, the corollas are covered in glandular trichomes which many of the gnats were glued to. Anywho, moving on.

Two brief stops encompass the last of my Kansas excursion, with 3 new observations, including the first cactus sighting. Or second day of travels ended just past the Kansas border in Colorado, in an abandoned state park.

Colorado

South Republican State Wildlife Area, formally known as Bonny Lake State Park, had its lake drained and doors shuddered in 2011 due to a 2003 supreme court decision that stated Colorado violated a water agreement with Kansas and they owed water to the tune of billions of gallons (Camper, 2015). All of the original buildings, roadways, shelters, etc. are left still standing, which gives the park a liminal state of being. There’s the feeling that people should be all around you, but nobody is; wildlife has taken over the former park. This was our resting spot for our second night.

First off, I need to state: S Republican State Wildlife Area has the most amount of mosquitoes that I have ever experienced in my life, despite the lake no longer being present. Every single second outside of the tent was spent trying to swat swarms of mosquitoes away from your body. Otherwise, fantastic place with fantastic flora adapted to a dry, sandy site. The habitat had a lovely mixture of eastern Colorado plain habitat and semi-desert shrubland.

Once again, the Oenothera were prevalent in the landscape. Three species made up the community around our campsite: O. serrata, O. lavandulifolia, and O. suffrutescens. These species are notoriously hawkmoth pollinated and the placement of the stamens & stigmas are so that the moths bump into them while sticking their long proboscis into the corolla to lap up nectar. Also, note the 4-part stigmas which are a fairly conserved trait across Oenothera.

Subchapter: The Posterchild of Coevolution

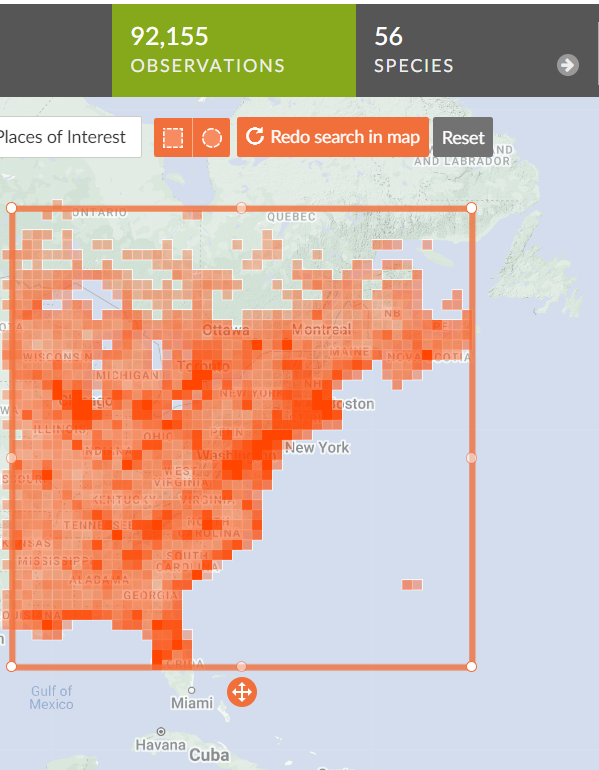

Primarily, the species I was most excited to see was Yucca glauca a member of asparagaceae that is emblematic of the southwest. Its sharp, leathery leaves scream ‘I’m tough, don’t mess with me.’ Other than its unique appearance, what excited me most about seeing Yucca in habitat is its famous co-evolutionary relationship with its pollinators, Tegeticula & Parategeticula moths (yucca moths).

A history dating back to 1872 by George Engelmann (Pellmyr, 2003), this coevolution has been well-studied and is one of the strongest examples of plant-pollinator coevolution. In summary, yucca moths are entirely dependent on Yucca species for their entire development. The moths emerge from their cocoons in the soil beneath a yucca, fly to yucca flowers where they scrape pollen off of their stamens, oviposit their eggs into the flower’s ovary, and then deposit the pollen on to the flower’s stigma (Pellmyr, 2003). The eggs hatch, eat some of the yucca’s seeds, and then emerge from the fruit, dropping on to the ground which completes the life cycle (Pellmyr, 2003). Now that is pretty sweet on its own, but that’s not the whole story. Let’s go deeper into plant sex, shall we?

Like many lepidopterans, the adult yucca moths do not eat; unlike other lepidopterans, yucca moths possess ‘tentacles’ which they use to scrape and hold the pollen from the stamens (Pellmyr, 2003). Next, the female moth, with its acute chemosensory organs, will detect if another moth has already oviposited on this flower, thanks to a helpful egg-laying pheromone. This answer affects the amount of eggs the female moth lays with more ovipositing events leading to less (or no) eggs (Pellmyr, 2003). This behavior isn’t just due to limiting intraspecific competition, the yucca flower will abort fruit that it senses has too many moth eggs inside (Pellmyr, 2003) (Moisset, 2024). The final act of the moth is to intentionally fertilize the flowers using the pollen stored on their tentacles (Pellmyr, 2003). By limiting the number of eggs laid on a single flower, the moths are encouraged to pollinate- and hopefully outcross- other flowers, as well as preventing the moths from consuming all of the seeds in a single fruit, thus increasing plant fitness. What an absolutely nutters coevolutionary relationship, but now on to other species.

Following our night in S. Republican State park, we drove almost non-stop through Colorado on our way to Arches National Park in Utah. In both of our opinions, the drive through the Colorado Rockies along route 70 was our favorite portion. I wish I had photos to share, but alas, I was the one driving (and its nice to just experience some moments without the addition of technology).

Before we leave Colorado, there were a few species growing in roadside ditches I want to highlight. Another example of why roadside botany can be so rewarding.

Utah

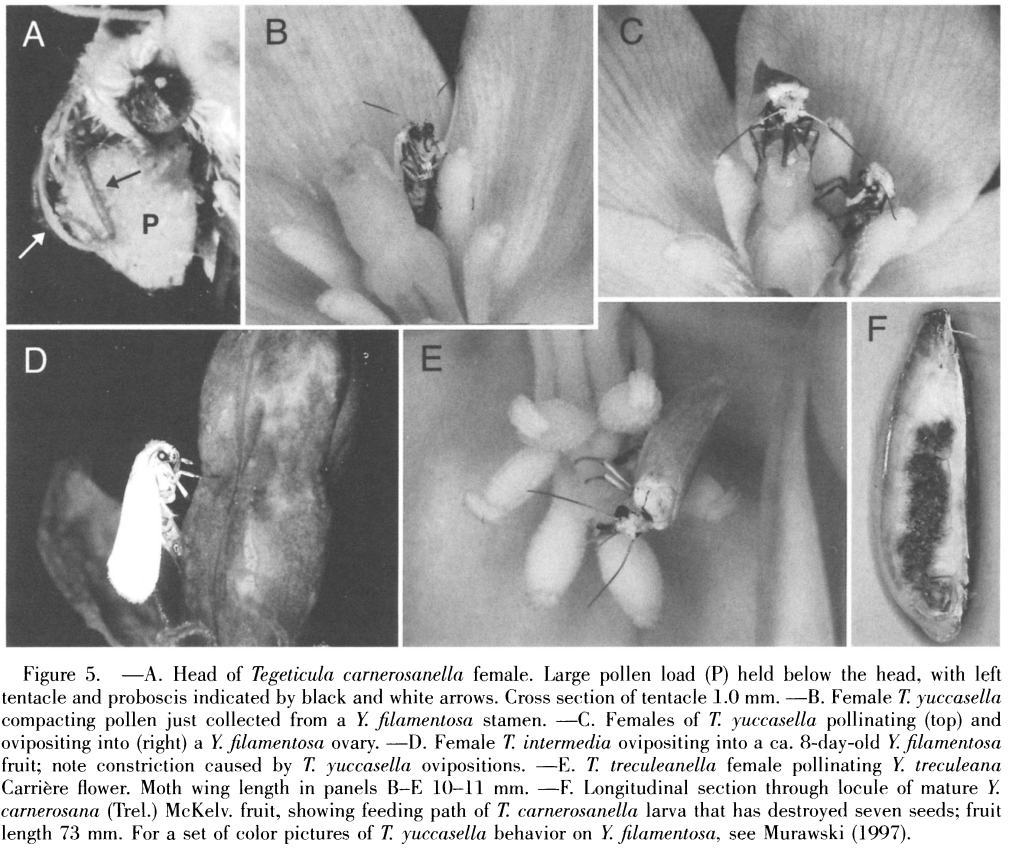

After passing through the Rockies, our goal was to see Arches National Park with the waning hours of evening sunlight that we had left. The soaring heights and white stratigraphic facades faded away into the shrublands of western Colorado, and then eventually, the technicolor ‘layer-cake’ mesas , buttes, and plateaus of Utah, (Mathis, 2018) (“Geologic Formations, 2024). This section of drive and the subsequent tour of Arches ignited my desire to know more about geology. I was surrounded by wonderous lithographic machines hundreds of millions years in the making and I felt so privileged to be observing them. So once again, let’s dig into the geology that shapes the plant communities.

Subchapter: Sandstone, Sandstone, and Would You Look at That, More Sandstone

Moab, UT is a land steeped in religious iconography and references (Moab, is a name that means, “Land beyond the Jordan.”). A holy place to both the people who currently and previously inhabited it. Even as a self-avowed agnostic-atheist I will admit I understand the geographical fervor. The landscape we now enjoy began its formation in the Jurassic period about 204 million years ago, and continued throughout the Tertiary period up to approximately 1.4 mya (“Geologic Formations, 2024). Ancient sediments from oceans and lakes (“Moab Fault,” 2023) were laid down and covered up in a repeating process. If not for the Moab Fault, this region would’ve stayed buried; but, seismic activity 65 mya began to shift, contort, and raise the buried sediment, ultimately displacing the area by 3,150 feet (“Geologic Formations, 2024) (“Moab Fault,” 2023). Now exposed and cracked, erosional forces could work their patient practice on the ancient sediments.

Arches National Park is of course, known for its preponderance of rock arches. These arches are made mostly of what we call the Entrada Sandstone, which is a part of the San Rafael Group (“Geologic Formations, 2024). After being raised from the deep earth, the porous sandstone would crack and erode with periodic rainfall and freezes, which would develop ‘fins’ of sandstone into archways (“Geologic Formations, 2024).

There is, of course, more to this story, but its not within my scope to cover it all. If you are interested then please follow my citations to your own educational betterment.

Subchapter: Desert Flora in Full Glory

The flora of Moab, UT, are desert-adapted species growing in a very porous substrate and subsisting off roughly 9 inches of precipitation each year (“Moab, Utah,” 2024). Otherwise known as ‘tough-bastards.’

Firstly, I’d like to discuss two species of should-be trees, Fraxinus anomala & Quercus welshii. Growing tall in the desert isn’t something you do; it takes too much water. Cue my excitement when seeing the Single-Leaved Ash & Tucker Oak, reaching a maximum height of 20 & 6 ft respectively. Back in my hometown of Ohio, these genera can reach over 100 ft. These species beautifully depict how a desert environment can shape a species.

There are few more taxa that I want to talk about here at Arches. First up, a taxa I’ve always wanted to see, Ephedra.

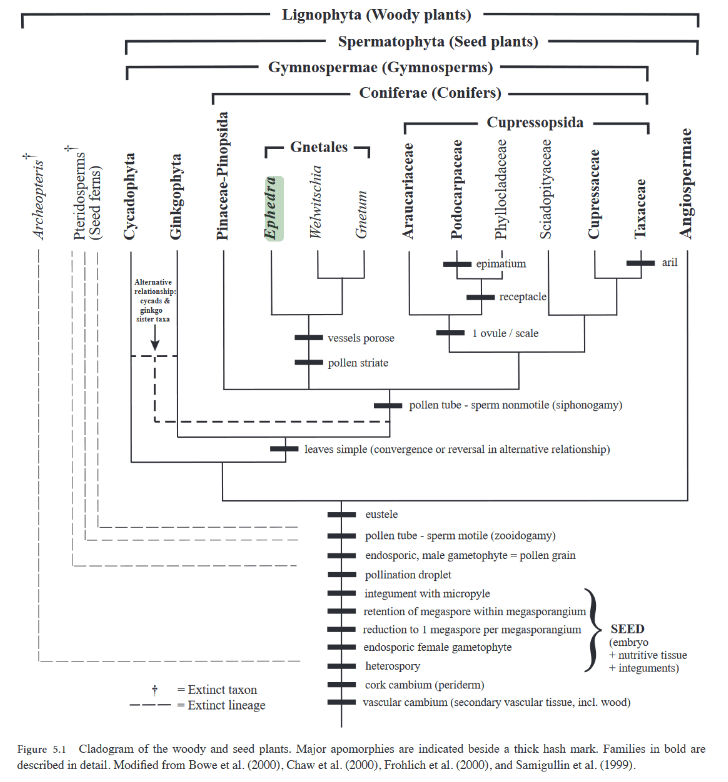

Ephedra are gymnosperms that are broadly distributed across arid regions. Technically speaking, Ephedraceae is one of the 3 groups that makes up the Gnetales, along with the other families: Gnetaceae and Welwitschiaceae (Simpson, 2019) (if you’ve never heard of Welwitschia mirabilis, click here).

Being a gymnosperm, Ephedra doesn’t produce any flowers, instead it reproduces in cones. In my picture above, you can see the yellow, male-cones within the nodes. Unlike other gymnosperms Ephedra– and the other gnetophytes- contain vessel elements, porose sections of vasculature which are a key distinguisher between coniferous wood and angiosperm wood (Simpson, 2019). According to Simpson’s Plant Systematics- 3rd Edition, this along with a smattering of other characteristics made botanists question Gnetales’ relationship to angiosperms, but ultimately nestled them sister to Pinopsida & Cuppressopsida after deciding the traits were apomorphic.

Other than Ephedra, several groups begin to make themselves known to me. Moving westward, I begin to notice taxa such as Nyctaginaceae (represented here by A. elliptica), Loasaceae (M. albicaulis.), Boraginaceae (Oreocarya spp.) become more prominent. Most excitingly though, the cacti diversity increases.

mojavensis

mojavensis

Fun fact, you may think of cacti as an essential member to deserts, but that is far from the truth. There are roughly 1,800 species of cacti and all but 1 are native to the Americas (Novoa, 2015) (Dimmitt, 2024); the exception is Rhipsalis baccifera, which scientists believe originated in the Americas but was dispersed by birds to the African continent. In my home state of Ohio, 3 cacti species are found isolated to inland sand dunes and sand barrens- Opuntia humifusa, O. cespitosa, and O. macrorhiza; that pales in comparison to western diversity. So far, I have seen at least 6 species of cacti- I say at least because I’m not confident in my ability to ID Opuntia species- over my botanical career. I hope to see more. In Arches NP, I witnessed two, Opuntia polyacantha & Echinocereus triglochidiatus ssp. mojavensis.

Cacti underwent an adaptive radiation in the new world from a common ancestor in the plant family Caryophyllales, and now have taken many forms to adapt to harsh, dry habitats. This is partly thanks to an adaptation to conserve water through the photosynthesis process called Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM). According to Heyduk et. al., in their 2016 paper, “Evolution of a cam anatomy predates the origins of Crassulacean acid metabolism in the agavoideae (asparagaceae),” the separate evolution of CAM has occurred at least 35 times in response to changes in life habit that require conservation of water. What’s different in CAM than normal photosynthesis (dubbed C3) primarily revolves around the opening of leaf pores (stomata) and the storage of sugar.

In C3 photosynthesis, the stomata are open during daytime to allow the process of photorespiration to occur; CO2 enters the stomata, water and O2 exits, which is flagrantly wasteful. Such flagrancy cannot be tolerated in the desert. So, CAM plants have adapted by breaking up their photosynthesis into a night and day cycle (not to be confused with the dark reaction of photosynthesis). During the daytime, stomata are closed to prevent the waste of CO2 and the concurrent transpiration of water. During nighttime, when temperatures are cooler, the pores open, CO2 is allowed in, and it is stored as a 4-carbon sugar called Malate to be converted into glucose during the day. All in all, a pretty nifty adaptation to have in the desert.

Finally, a brief touch on cacti pollination. Cacti flowers all look fairly similar, despite having a diversity of pollinators across animal groups. Beetles, bees, bats, birds, moths, and flies have all been known to pollinate cacti. Cacti flowers are an equal-opportunity pollen source.

Our tour of Arches NP ended, and we needed to find a place to rest again. A clear night away from civilization allowed me to try nighttime photography for the first time.

If you thought Utah was over, you would be wrong. Another example of roadside botany at its best is coming right at ya! On our longest day of driving, we made several roadside stops because of some crazy plant I wanted to see, or, in this case to sightsee. A sign on I-70 read, “San Rafael Reef View Area.” We were elated to see a fossilized, prehistoric reef, so we pulled over. As I darted to see some plants I spotted, my travelling companion went over to read the signage, and came back to me with news. This was a reef indeed, not biological, but chemical. This area was used as a rather successful uranium mine back in the day, but is now a tourist attraction, and home to several rare plants. We spent maybe 20 minutes walking around before we had to get back on the road. Most notably, a species on the IUCN Red List (near threatened) (Contu, 2010), Hoffmannseggia repens.

Otherwise known as creeping rush pea, Hoffmannseggia repens (boo, eponymic generic epithet), is endemic to SE Utah, and that’s it. If this plant looks familiar to you, that may be because it is a part of the subfamily, Caesalpinioideae, which contains the familiar groups like Senna and Chamaecrista.

Finally, a few more observations before we leave Utah in the desert-dust. My second Yucca, Y. harrimaniae and the large-flowering for its small size, O. cespitosa were exciting finds, as well as my new favorite brassica, S. pinnata with its huge raceme of typical brassica flowers. What excited me even more were two species of buckwheats, E. shockleyi & E. wetherillii. I love clump-forming buckwheats like the former, but it is really the latter that steals my heart here. According to INaturalist, there are 33 observations of E. wetherillii, all in Utah, although the plant doesn’t have a current conservation status listing. There isn’t much info available online about this species either. I’m willing to guess this is another species endemic to the San Rafael area. I do love a mystery. Unfortunately, this post is already hitting 20 citations and I have the two biggest sections to cover, so we have to keep moving to…

California

If you thought that we would be heading to Nevada next, which logically comes geographically after Utah, you would be dead wrong. I did travel through Nevada to get to CA, but CA is not where the journey ended, so, you’ll have to wait.

Before I made my home in Reno, NV, we travelled into the Sierra Nevada to explore the national forests around Lake Tahoe. The geology of the Sierra Nevada is quite complex, in fact, parts of its natural history are still being debated in scientific circles. To explain everything in detail would require more space and time than I am willing to commit, and likely more attention than you may have for such a grandiose topic at this point. Here is a summarization.

Subchapter: Sierra Nevada, A Natural History

The Sierra Nevada is a large mountain range that runs north to south for 400 miles, with a general increase in elevation as you move southward, and contains the highest peak in the contiguous US, Mt. Whitney at 14,505 ft (“Geology of the Sierra Nevada,” 2023) (“Sierra Nevada,” 2024). Much of the rocks you’ll find across the Sierra Nevada will be granite, or other metamorphic rocks; and the preponderance of the beautiful, white structures is thanks to its formation in the Nevadan Orogeny (“Nevadan Orogeny,” 2024), a fancy term that means mountain formation. Approximately 215 mya (“Geology of the Sierra Nevada,” 2023), the Farallon oceanic plate subducted underneath the N. American plate, bringing ocean water underground with it. Superheated water began to melt the N. American plate and volcanic arcs formed along the infant Sierra Nevada (“Geology of the Sierra Nevada,” 2023) (“Sierra Nevada,” 2024). In addition, during the time of the Nevadan Orogeny, the oceanic plate brought foreign arc terranes that were too buoyant to subduct underneath the continental plate and thus became accreted to the forming Sierra Nevada (“Nevadan Orogeny,” 2024). Underground magma from the volcanic arc activity slowly melted the sedimentary rock present in the continental crust and then cooled over long periods, which allowed crystals to form and resulted in the large granitic batholiths of the Sierra Nevada (“Geology of the Sierra Nevada,” 2023) (“Sierra Nevada,” 2024).

Eventually, around 30 mya the Farallon plate was completely subducted, the mid-ocean ridge covered and the NW-moving Pacific plate created the now San-Andreas fault (“Geology of the Sierra Nevada,” 2023). Then, at 10 mya, the last major form of uplift (although the Sierra Nevada are still uplifting today) brought more granitic material beyond the surface along with the lowering of the Nevadaplano (more on that later); and finally, at 2.6 mya glaciation carved out large sections of the Sierra Nevada range, resulting in the U-shaped valleys, glacial horns, and other scenic formations we enjoy today (“Geology of the Sierra Nevada,” 2023).

Lake Tahoe, and its surrounding national forests, is here today thanks to these geological processes of faulting, volcanism, and glaciation (“Geology of the Lake Tahoe Basin.” 2024). Snowmelt feeds this large mountain lake, and runoff from the lake feeds into the Truckee river which brings life down into Reno, NV. Fun facts about Lake Tahoe. Its maximum depth is 1,645 ft, which makes it the 3rd deepest in the US, and 10th in the world. Lastly, despite the shoreline of Lake Tahoe sitting around 6,200 ft in elevation, the bottom of the lake is at a lower elevation than the adjoining Carson Valley in Nevada (“Geology of the Lake Tahoe Basin.” 2024).

Subchapter: Desolation Wilderness

Our hikes took us to the El Dorado National Forest and Tahoe National Forest sides of Lake Tahoe. Both were beautiful and amazing to behold, but between the two, we’re more of a fan of El Dorado. Tahoe was very developed, bougie, and overran with “private property, no beach access signs.”

Our first stop was on the south side of Lake Tahoe, in the Desolation Wilderness. The trail we took takes you up to Mt. Tallac, a soaring 9,739 ft in elevation, and the entire trip could take you all day. We did not unfortunately have all day. One day I would like to return to complete it. The trail offers scenic views of Mt. Tallac of course, steep mountain valleys, Lake Tahoe, and Fallen Leaf Lake.

Near the trailhead, the ground was covered in blooming wildflowers with multitudes of busy pollinators and foraging insects flitting between them. The pine needles hosted a community of Lupinus argenteus, Calyptridium monospermum, and Castilleja applegatei. This was a good omen of botanical diversity to come, and we didn’t have to wait too long. Quickly I began to notice several species of Ribes along the trail. By far my favorite, Ribes roezlii, has maroon, 1 cm wide flowers hanging profusely off of the stem. The structure of their flowers remind me, at least superficially, of the buzz-pollinated structure many Solanaceous species present (see Solanum xanti below). The stamens and pistil protruding from the sheathe of pink petals and reflexed maroon sepals do seem to suggest a good spot for bees to clamber on, but according to a 1954 study from the USFS, the flowers are wind-pollinated. I find this suspect.

Moving up further we encounter another Lupinus, L. grayi growing on a ridge overlooking Fallen Leaf Lake. It is on this 7000 ft. ridge where most of the other interesting species make themselves known to us. The shrub cover is mostly Arctostaphylos patula, but also has a few species of Ceanothus. What really got me excited though were two herbaceous species I had scouted on INat before I even left Ohio.

Subchapter: The Birds and the Bees

Ipomopsis aggregata & Penstemon speciosus are two very showy species depicting two classic pollination syndromes. Long, red corolla tubes are a key indicator of hummingbird pollination, whereas showy, wide corolla tubes are usually key to bees, typically in the genus Bombus. It is observed that hummingbirds are the most frequent visitors to I. aggregata, and P. speciosus is pollinated by bees, but that’s not the whole story. While they both may be adapted towards restricting other pollinators, it isn’t a perfect system. In a pollination study around I. aggregata, researchers indeed found hummingbirds to be the most frequent visitor to their flowers, but, to their surprise, long-tongued bumblebees were more efficient pollinators (Mayfield et al, 2001). The bumblebees deposited 3 times as much pollen, and resulted in 4 times as much seed production than the more frequent hummingbirds (Mayfield et al, 2001). This story continues in Penstemon.

Most Penstemon are bee-pollinated, but a good portion are adapted to hummingbirds. Sometime in the past, the character traits became more specialized towards hummingbirds. Can you take a guess as to what has to change from the above pictures?

P. barbatus is one such hummingbird pollinated species. The corolla tube has tightened and the color has shifted to red. It bears some resemblance to the Ipomopsis flower, echoes of evolutionary selection pressures. (Photo credit to Fireflyforest.com, 2024)

Hummingbirds will visit bumblebee-syndrome Penstemons on-occasion- a food source is a food source after all- and a study on pollinator shifts by a group of researchers (including one of my former professors Andrea Wolfe, who makes some mean vegan food) looked into what factors lead to a change in pollinators between bees and hummingbirds (Wilson et al, 2006). This study mostly focused on the above hummingbird-Penstemon, and a bee-adapted species, P. strictus. In this case, they found bees did not visit P. barbatus, nor were they even able to contact the stamens when they trained bees to visit the flowers; P. strictus is another story. Bees were better pollinators than hummingbirds (makes sense). The pollen grain removal was only slightly worse in hummingbirds, the hummingbirds deposited less grains per flower (also makes sense), but, the hummingbirds deposited pollen on far greater stigmas than the bees (which they claim is likely due to the cleaning behavior of bees, leading to a drop-off of deposition after the first few visits) (Wilson et al, 2006). A picture starts to come together here. Hummingbirds, despite being less frequent and less efficient pollinators, can pollinate more flowers. Consistency is important. It may take just a few shifts in character traits to start favoring hummingbirds over bees. Once again, there could be more expounded on, but I am going to move on to another exciting plant, manzanita.

Subchapter: Desolation Wilderness, Continued

Manzanitas are an important species for pollinators and herbivores alike. They are members of the blueberry family, Ericaceae. As I said before, this shrub formed thickets that made up the majority of the shrub layer on the mountain-ridge. The waxy-green, ovate leaves, stark-white dead branches, and smooth, cinnamon-colored live stems were quite stunning to behold. There weren’t any plants in bloom, so I’ve included a picture of A. uva-ursi below to show the structure of this taxa’s flowers. My adoration for the family of Ericaceae continues once again.

Next, on this trail I observed possibly the most stunning example of Juniper I have ever laid eyes on, the Sierra Juniper, Juniperus grandis. Junipers have always been tough-bastards that can thrive in shitty, often disturbed soils. The below example is exemplary of the genus’ ability to hang on. Most branches are dead, yet the top growth is still churning. As I looked closer at this beauty, It became quickly apparent that there was more happening here. Erupting from the branches were wild lime-green stalks that I immediately recognized as mistletoe. Mistletoes are broadly hemiparasites, still producing their own sugar through photosynthesis, but dependent on their host for water and nutrients. Its this fact that means mistletoes usually aren’t detrimental to their host’s health. I wish I could’ve seen it in bloom, but oh well, its for another time.

We finally said goodbye to the Desolation Wilderness and headed north to buy a bear canister as neither of us were aware they were required for camping. My midwestern self was used to making bear hangs to avoid black bear scavenging and had came prepared, but, I was unaware that the west coast bears had figured that trick out. Before we left completely though, on the road we spotted three species I desperately wanted to see, so once again, the car was pulled over and photos were taken.

Snowplant, otherwise known as Sanguinea sarcodes is a holoparasite, requiring everything from its host. It also is member of Ericaceae, and subfamily Monotropoideae (do you see the floral resemblance to ghost pipes?). Poster-child of western forests, snowplant is endemic to the Sierra Nevada and Cascades, a speciation thanks to the formation of the Nevadan Orogeny.

Mountain Pride, otherwise known as Penstemon newberryi is an absolutely stunning member of its group. Its name is fitting, it loves to grow out of rock-crevices at high elevation and looks absolutely gay. I have no more to say about this species, other than damn, what a plant.

Lastly, a shrub-form of the family Fagaceae, Chrysolepis sempervirens, the bush chinquapin. There are two members in the genera and I have always wanted to see it in person.

Our last hurrah in California was closer to Tahoe NF, on the Five Lakes Trail.

Subchapter: Five Lakes Trail & Adaptations to Water Scarcity

We wanted to camp somewhere around Lake Tahoe, and after buying our requisite bear can, we looked for a good spot. After seeing a place called Alpine Meadows on the map, I was hooked! Early June meadow plants in the Sierra Nevada, sign me up! Cue our disappointment when we pulled up to Alpine Meadows only to find out it is in fact, a ski resort. After some brief frustrations we looked across the street and found suitable lodging: a hike up a mountain on the Five Lakes Trail.

4.8 miles and 1,095 ft of elevation gain takes you up through the Granite Chief Wilderness to a series of five montane lakes at 7,550 ft. The Pacific Crest Trail makes its way through the SW side of these scenic lakes. At our time of arrival, snowmelt was still continuing and the lakes had warmed enough that a massive frog breeding event was occurring. Thanks to the snowmelt, roaring waterfalls were cascading down granite outcrops, which provided us with ample sources of water. For most of the hike, the plant life was similar to that of Desolation Wilderness, but there were a few new faces.

Most of the plants along the trail were growing out of piles of rocks or in crevices. Lithophytes are absolutely fascinating organisms. The ability to adhere yourself to a crack in the rock and collect/conserve water is an incredible adaptation. Three lithophytes I was elated to see were all species of ferns, in three different genera, although they all belong to the same family, Pteridaceae. These ferns have developed the ability to grow when water is available, usually when snowmelt runs down the mountain, and then die-back and wait when drought comes. In addition, some species like M. gracillima also have many tiny hairs around their pores and will curl their fronds to reduce water loss through transpiration. Who needs CAM when you’re just a tough ol’ fern?

Other than the ferns, there were several other species I was excited to see, such as Asclepias cordifolia and Streptanthus tortuosus, but by far my favorite plants were Sedum obtusatum and Ceanothus prostratus. As an Ohioan, the only succulents we get to see are those grown indoors, or if you’re lucky Sedum ternatum. It is wild to me that these cotton-candy-hued succulents grow naturally. Also, if you hadn’t figured it out already, Sedum undergo CAM photosynthesis like the cacti prior. Lastly, C. prostratus, as its specific epithet suggests, grows as a creeping mat. Combined with its thick, waxy leaves, these adaptations help conserve water on the mountain slopes. In addition, the ornate, purple flowers are something to behold. The structure of these flowers can be a little confusing, but the 5 spoon-shaped structures are the petals and the 5 inward-bent structures are its sepals.

In the final ode to California, I want to highlight the most stunning life-form we saw, a lichen, Letharia vulpina. At around 7000′ in elevation this lichen began covering the trunks of Abeis concolor trees, growing on spaces where branches had died-back and the branch collar had hung on, or occasionally on branches. The specific-epithet, vulpina, refers to the toxic-effect of a chemical these lichens produce, vulpinic acid, and human’s usage to kill predators like foxes with the lichen by mixing it into bait (1996). Pretty gruesome for such a pretty organism, but usually anything brightly colored in nature is trying to warn you it means harm.

I know at some point I will be returning to California to hike the Sierra Nevada and be amazed by its endemism, and I look forward to that day. But, all things must pass and as we passed over the border into Nevada. Coming down Mt. Rose, we spotted a prostrate Lupinus, and that is something I definitely cannot pass up. So once-again, the car was pulled over to see Lupinus lepidus.

Growing at 8,320 ft in elevation, water loss from wind is this Lupine’s greatest concern. So growing low to the ground and being covered in tiny hairs helps keep this Lupine’s water from being siphoned off.

This absolute beauty of a Lupine is a beautiful goodbye to California and a welcoming hello to my new home.

Nevada

The Intermountain West. A land full of disconnected mountain chains. Imagine if Nevada was made out of a giant bedsheet and a giant human took the edges of the state and pushed the ends together. In the middle you would have large ripples that formed. That is essentially Nevada (except that analogy sucks, and you’ll see why soon). In fact, according to my super-cool new technical supervisor, as well as an editorial from the Great Falls Tribune, Nevada is the state with the most mountain ranges (Tribune Edit Board, 2017). The thing is, I looked into the source of that, and the only good info I can find is their source, which is blurtit.com, a Q&A community (Blurtit, 2024); not exactly a reliable source. Is this one of those cases where an incorrect tidbit gets spread around so much that it becomes “truth?” I’m not sure, but if you look at a topographic map of Nevada it certainly seems true, so I’m gonna trust my new, cool boss.

Before I even was offered this position, my understanding of Nevada was threefold.

- 1. Nevada is pretty much just desert (I’ve played Fallout New Vegas, so of course I know).

- 2. Las Vegas was pretty cool to visit.

- 3. The rest of the state has nothing going on.

Boy, was I incorrect, but not about the desert part, that much is true.

Nevada rests in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada. Air currents that come off the pacific and bring humid air cannot get over the tall mountain range, which makes Nevada the driest state in the US (Price, 2003). Combined with the sky-island habitats formed from the formation of multitudes of isolated mountain ranges, and you have a perfect recipe for endemism. For the final time, let’s understand how this geological wonder formed.

Subchapter: Fall of the Nevadaplano

Rise of the Humboldt-Toiyabe

In California, I mentioned the term, ‘Nevadaplano,’ which is a term referring to the ancestral state of the Basin and Range region, which means “Nevada plateau.” Prior to the Farallon plate subducting underneath the N. American plate, the western US was just that, a plateau. The formation of the Sierra Nevada, volcanic activity across the Nevadaplano, and the antiparallel motion of the Pacific plate and N. American plate is what gave us our modern-day Nevada (Price, 2003) (“Basin & Range, 2024) (Lundstern & Miller, 2021).

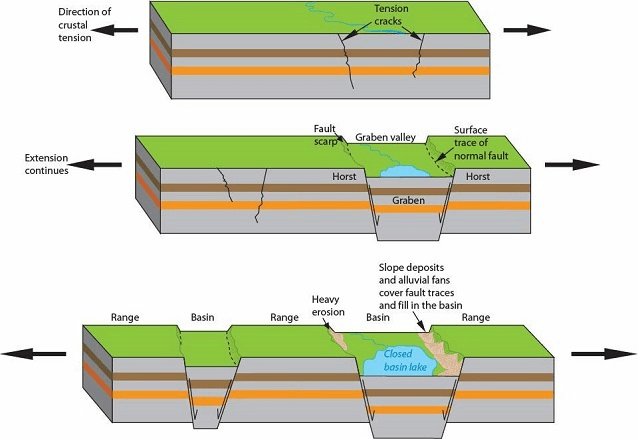

As the Farallon plate subducted forming the Sierra Nevada, it began to fall deeper and deeper into the asthenosphere, which caused the Nevadaplano to compact into the westward-moving N. American plate and the crust to thicken (“Basin & Range, 2024) (Lundstern & Miller, 2021). A steeper dipping Farallon plate caused magmatism within the thickened crust, resulting in volcanism over 10 million years (Lundstern & Miller, 2021) (Price, 2003). Then, the now antiparallel moving Pacific plate and N American plate caused extensional faulting, resulting in what is called Horst and Graben topography (Lundstern & Miller, 2021) (“Horst and Graben,” 2020). Essentially, the thickened crust failed as the Nevadaplano was pulled in two different directions, and large valleys (basins) sunk as large mountains (ranges) raised, and eroded material filled in the gaps. This is the process that gives us the Great Basin, and it too has a more technical term, Cordilleran Orogeny. Once again, there is much more to this, but I am no geologist, just a botanist with a passion for learning half of a story.

If that seemed like a headache to you, it should. It was for me too. After researching the formation of the Sierra Nevada, I thought the sinking of the Nevadaplano would be a cake-walk. Ha! Thankfully, I do actually have a cake-walk for you now, Nevadan flora.

Subchapter: Lily in the Sky Islands With Delphiniums

So far I have identified around 83 species in Nevado, with the greatest source of IDs around Reno. I will not subject you to all of them. Instead I would like to talk about a few groups. If you want to view them all, please go to my INat and correct some of my terrible IDs. I am @liliumoryza.

Eriogonum

According to Inaturalist, there are 76 species of Eriogonum in Nevada, I have seen 8 species so far, 5 of them in Nevada. The west has provided perfect habitat for a speciation for buckwheats. Incredibly important to the intermountain west, buckwheats are fantastic food sources for pollinators and lepidopteran larva; and the seeds are often eaten by mice and birds (Taylor, 2003). Eriogonum grow in a diverse range of habitat and can tolerate incredibly toxic/difficult soils, such as salt basins or soil laden with broken down serpentine.

As genetic testing continues on plant populations expect greater divisions within Eriogonum as evidence points to previously considered subspecies actually being distinct (Grady, 2011).

Two species below I would like you to pay special attention to for their divaricating structures, E. heermannii and E. nidularium. Divaricating branches often have minimal to small leaves and are likely an adaptation to deter herbivory. While I am not convinced the latter buckwheat’s structure is an anti-herbivory adaptation, I am more certain with the former. Tougher, woodier, and sharper stems are a dead giveaway, especially with how tightly the shrub conceals its leaves. Many buckwheat flowering scapes are highly branched, so it is likely that E. nidularium is just that. See Psorothamnus polydenius for a definite example of anti-herbivory divarication.

Castilleja

If you’ve followed me for a while, you know I love Castilleja. They are infamous hemiparasites of both grasses and forbs. Very showy plants but not for the reason you may expect. The majority of the red coloration is due to protective, modified leaves, known as bracts and sepals. The petals are fused together and are usually inconspicuous within the fused sepals. Take a second and admire this unique flowering structure. If you remember just one chapter ago from our discussions on Penstemon & Ipomopsis, what would likely be the primary pollinator of Castilleja?

Calochortus

My name is Lily, right? Of course I have always wanted to see one of the most diverse and widespread lily groups in N. America. I have long heard about these charismatic lilies and their species radiation. Like the previous two examples, the Mariposa lilies grow in a variety of habitats and can tolerate some toxic/difficult substrates.

Unlike most lilies, the 6 tepals of Calochortus are differentiated into a smaller whorl, and a larger whorl of 3 each. One could consider the larger ones to be petals and smaller to be sepals. In Calochortus the innermost part of the tepals are highly important for identifying species, as they are usually highly decorated with pigmented hairs or colorful spots. Can you spot the oh-so-slight difference between the 2 species below?

The Rest

There are many major groups within Nevada. To cover all of them here would take this blog post towards short-story territory. So, here are a few of the rest of my favorite finds and other important groups to the intermountain west that I have encountered. No commentary in this grouping, but take a keen eye to the diversity and adaptations these desert plants have made to living in the driest state in the US. Not nearly as lifeless and barren as one might think.

So Long, and Thanks For All the Fish.

The decision to leave my job as a tree worker and move out west to pursue botany was a difficult one, and probably not for the reason you are thinking. I had been an arborist for 3 years; I commercially sprayed pesticides, removed trees, and ornamentally pruned trees & shrubs. My final rate was $25/hr, full disclosure. The job I am in now, pays $8 less. Sure there are other benefits, but it isn’t about the money (although I do believe we should be funding our natural resources better as a nation). As an arborist I made fantastic friends who I saw and worked with everyday, but it wasn’t the camaraderie that made it hard to leave either. I had built a home in NE Ohio with my two partners, and I do desperately miss it, but again my position lasts only 6 months.

What made it difficult was my choice in position. For the first time in my botanical career, I had the choice on where to work: Giant Sequoia NF, Joshua Tree NP, or Humboldt-Toiyabe NF. I chose as we know, Humboldt-Toiyabe.

There is a philosopher named Kierkegaard who wrote once about losing part of yourself in two different ways: in the finite, or the infinite. This is likely a misinterpretation of his work, but it is the way that I have interpreted it and that has helped me in my decision making process. When you sit and fret about all of the infinite possible ways your life could turn out, you lose a bit of yourself in the process, not realizing what is real, or finite. Likewise, if you spend the same time fretting over the reality of your situation, and not the infinite potential you possess, then you block yourself off from that infinitude. Before I was offered these three positions- at the same time mind you, that truly was a clusterfuck- I was losing myself in the infinite. I had tried for 5 years since my graduation at OSU to get something going in botany, and I tried every avenue I could in Ohio, so, I was stuck in the reality of just getting by at my tree-work job that I did not enjoy. I had blocked myself off to the potentiality of work outside the Midwest. Then, 3 jobs at once, in the west. Suddenly, the script flipped. For a brief moment I was lost in the finite, and then, clarity.

After a reading recommendation from the OSU Herbarium Curator back in 2019, The Song of the Dodo, by David Quammen, I became enamored with island biogeography and the ways it allows taxa to rapidly speciate, usually in quite extravagant manners. The decision became easy, Nevada. The Great Basin is filled with unconnected mountain chains, separated by 1000s of feet in elevation, many miles, and often completely different rock compositions on the ranges. Each chain a different island in the sky. What better way to see how evolution adapts species than in the largest national forest in the contiguous US, with the most mountain ranges than any other state.

And hey, thank you for making it this far. I hope you learned something new worth sticking around for. Stay tuned as I become the botanist I was meant to be.

Citations

- “Basin & Range: Structural Evolution- Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology.” SAGE, NSF, http://www.iris.edu/hq/inclass/animation/basin__range_structural_evolution#:~:text=The%20basins%20(valleys)%20and%20ranges,weight%2C%20as%20it%20pulled%20apart. Accessed 17 June 2024.

- “Cam Plants – Definition, Evolution, Photosynthesis, Examples, and Faqs.” GeeksforGeeks, GeeksforGeeks, 12 Jan. 2024, http://www.geeksforgeeks.org/cam-plants/.

- Camper, T. “Colorado’s Bonny Lake State Park Loses Its Lake.” Camp Out Colorado, 16 Feb. 2015, http://www.campoutcolorado.com/colorados-bonny-lake-state-park-loses-its-lake/.

- Contu, S. “The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 11 Aug. 2010, http://www.iucnredlist.org/species/19891635/20078730.

- Dimmitt, Mark A. “Cactaceae (Cactus Family).” Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, http://www.desertmuseum.org/books/nhsd_cactus_.php#:~:text=The%20cactus%20family%20is%20nearly,regions%20of%20the%20Old%20World. Accessed 15 June 2024.

- “Geologic Formations.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, home.nps.gov/arch/learn/nature/geologicformations.htm. Accessed 12 June 2024.

- “Geology of the Lake Tahoe Basin.” Forest Service National Website, Lake Tahoe Basin MGT Unit – Learning Center, http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/ltbmu/learning/?cid=stelprdb5109570. Accessed 16 June 2024.

- “Geology of the Sierra Nevada.” Yosemite Field Station, 17 July 2023, snrs.ucmerced.edu/natural-history/geology.

- Grady, B. R., and J. L. Reveal. “New combinations and a new species of eriogonum (polygonaceae: Eriogonoideae) from the Great Basin Desert, United States.” Phytotaxa, vol. 24, no. 1, 26 May 2011, https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.24.1.5.

- Heyduk, Karolina, et al. “Evolution of a cam anatomy predates the origins of Crassulacean acid metabolism in the agavoideae (asparagaceae).” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, vol. 105, Dec. 2016, pp. 102–113, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2016.08.018.

- “Horst and Graben (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 22 Apr. 2020, http://www.nps.gov/articles/horst-and-graben.htm.

- Horton, J.D., C.A. San Juan, and D.B. Stoeser, 2017, The State Geologic Map Compilation (SGMC) geodatabase of the conterminous United States: U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 1052, doi: 10.3133/ds1052. Accessed 11 June 2024.

- Lillie, Robert J. Subduction zone of the Farallon plate and North American plate. 2020. Transform Plate Boundaries, National Park Services, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/geology/plate-tectonics-transform-plate-boundaries.htm. Accessed 16 June 2024.

- “Little Lost Creek Conservation Area.” Missouri Department of Conservation, mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/places/little-lost-creek-conservation-area. Accessed 11 June 2024.

- Lundstern, Jens-Erik, and Elizabeth Miller. “GSA Cordilleran Section Meeting 2021.” Stanford, ResearchGate, Jan. 2021, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352915800_THE_NEVADAPLANO_WHEN_WHY_AND_HOW_HIGH. Accessed 17 June 2024.

- Mathis, Allyson. Moab Happenings Archive, Feb. 2018, http://www.moabhappenings.com/Archives/Geology201802WhatsInAName.htm#:~:text=Most%20of%20the%20rocks%20found,easily%20seen%20as%20broad%20sheets.

- Mayfield, M, et al. “Exploring the ‘most effective pollinator principle’ with complex flowers: Bumblebees and Ipomopsis Aggregata.” Annals of Botany, vol. 88, no. 4, Oct. 2001, pp. 591–596, https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.2001.1500.

- “Moab Fault.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 6 Nov. 2023, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moab_Fault#cite_note-:3-5.

- “Moab, Utah.” MOAB, UTAH – Climate Summary, wrcc.dri.edu/cgi-bin/cliMAIN.pl?utmoab. Accessed 15 June 2024.

- Mochizuki, Ko, et al. “Adaptation to pollination by fungus gnats underlies the evolution of pollination syndrome in the genus euonymus.” Annals of Botany, vol. 132, no. 2, 25 July 2023, pp. 319–333, https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcad081.

- Moisset, Beatriz. “U.S. Forest Service.” Yucca Moths (Tegeticula Sp.), Forest Service, http://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/pollinators/pollinator-of-the-month/yucca_moths.shtml. Accessed 11 June 2024.

- Nash, Thomas H. Lichen Biology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1996, pp. 178–179, https://books.google.com/books?id=P9y60ac0wbMC&pg=PA179#v=onepage&q&f=false. Accessed 17 June 2024.

- “Nevadan Orogeny.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 21 Mar. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nevadan_orogeny.

- Nichols, Jeffrey D. “The Founding and Naming of Moab.” History To Go, Sept. 1995, historytogo.utah.gov/founding-of-moab/#:~:text=William%20Pierce%2C%20one%20of%20the,Moab%20as%20the%20county%20seat.

- Novoa, Ana, et al. “Introduced and invasive cactus species: A global review.” AoB PLANTS, vol. 7, 1 Jan. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plu078.

- “Observations, Oenothera [West].” iNaturalist, http://www.inaturalist.org/observations?nelat=51.68506905129004&nelng=-60.50405612460325&place_id=any&subview=map&swlat=27.2335019807471&swlng=-92.84780612460325&taxon_id=48626. Accessed 11 June 2024.

- “Observations, Oenothera [East].” iNaturalist, http://www.inaturalist.org/observations?nelat=51.84824627346314&nelng=-93.02358737460325&place_id=any&subview=map&swlat=27.467698210453438&swlng=-125.36733737460325&taxon_id=48626. Accessed 11 June 2024.

- Pellmyr, Olle. “Yuccas, Yucca Moths, and coevolution: A Review.” Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, vol. 90, no. 1, 2003, p. 35, https://doi.org/10.2307/3298524.

- Penstemon barbatus – Beardlip Penstemon. Fireflyforest, https://www.fireflyforest.com/flowers/1870/penstemon-barbatus-beardlip-penstemon/. Accessed 16 June 2024.

- Price, Jonathon G. “Geology of Nevada.” Betting on Industrial Minerals, Proceedings of the 39th Forum on the Geology of Industrial Minerals, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, Sparks, NV, 2003. Special Publication 33.

- “Sierra Nevada.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 12 June 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sierra_Nevada.

- Simpson, Michael. “CHAPTER 5 EVOLUTION AND DIVERSITY OF WOODY AND SEED PLANTS.” Plant Systematics, 3rd ed., Academic Press, Cambridge, MA, 2019, pp. 131–132.

- Taylor, Ronald J. “Buckwheat Family.” Sagebrush Country A Wildflower Sanctuary, 8th ed., Mountain Press, Missoula, Mt, 2003, pp. 28–32.

- Tribune edit board. “The Edge: And the Most Mountainous State Is…Nevada?” Great Falls Tribune [Montana], 16 June 2017.

- Wagner, Warren, et al. “Taxonomic Changes in Oenothera Sections Gaura and Calylophus (Onagraceae).” PhytoKeys, Pensoft Publishers, 7 Nov. 2013, phytokeys.pensoft.net/articles.php?id=1488.

- Wilson, Paul, et al. “Shifts Between Bee and Bird Pollination in Penstemons.” Plant-Pollinator Interactions: From Specialization to Generalization, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, 2006, pp. 46–64.

- “What Is the Most Mountainous State in the United States?” Blurtit, travel.blurtit.com/76786/what-is-the-most-mountainous-state-in-the-united-states. Accessed 17 June 2024.

Leave a comment