May into June is a wonderful time to botanize in the Midwest. Warming temperatures, lengthening days, and increased rainfall- although this year less so- produce an affluence of plants in bloom. May in the Midwest, although, can still dip into freezing temperatures or potential snowfall, so, cold-tolerance adaptations are a necessity for May plants. Orchids may not be your first idea of a cold-hardy plant, but Lady Slipper orchids bloom early as the temperatures begin to warm.

The genera of Lady Slippers, Cypripedium, are all defined by one shared characteristic: their pouch-like labellum that (to some) resembles a slipper. As of now, there are approximately 50 species and 7 wild hybrids that are accepted. Although there are several hybrids that have arisen from the sympatry of these species, only one of which I have been able to see in person. I will only be discussing the straight species here.

Ohio has 4 species of Cypripedium:

- Cypripedium acaule

- Cypripedium candidum

- Cypripedium parviflorum

- Cypripedium reginae (my personal favorite)

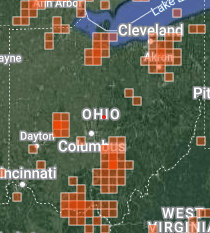

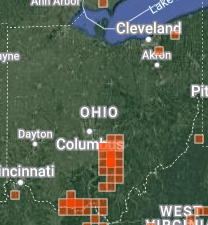

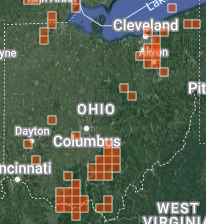

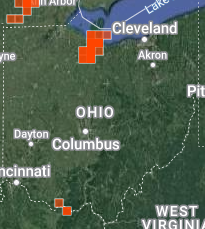

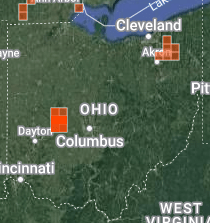

Our Cypripediums grow in rather specific habitats, which make them a skosh difficult to find if you don’t know where to look. It doesn’t help that their range in Ohio has decreased dramatically since our anthropogenic expansion has either eliminated or fragmented their habitat. The photo on the right is the disjunct distribution of the genus Cypripedium in Ohio as of 5/20/23 (INaturalist).

Cypripedium acaule & C. parviflorum are most often located within rich, upland, wooded slopes with slightly acidic soils, nestled into the leaf litter. Quite often in pine forests. Although, I have seen C. parviflorum located in wetter areas along streams, wet prairies, or other wetlands. In Ohio, these two species are often seen within the same region. The greatest population density of C. acaule & C. parviflorum are in southern Ohio within the unglaciated Appalachian foothills.

C. candidum is found in near full sun in alkaline prairies and fens. In Ohio, C. candidum is almost solely found within the remnant Sandusky prairie, with thousands of members seen in this one prairie. Interestingly, I observed more members within the mowed, walkable portions than the adjacent, untamed tallgrass. There is a small population found near the Ohio-Kentucky border along the hemiparasitic Castilleja.

Lastly, C. reginae grows mostly in alkaline fens, but is also sometimes found in wooded swamps and riverbanks. To see these guys in Ohio, you’ll have to travel to Cedar Bog, a misnamed fen, near Dayton, OH, or the NE, where fragmented kettle bogs and fens are weaved within the sprawling urban landscape.

Since we have gotten habitat and distribution out of the way, it’s time to get into what’s really interesting, flower morphology and pollination. What, you really only expected me to talk about habitat? This is WPSW for fuck’s sake; plant sex is our jimmy-jam.

All Cypripediums are variations on a theme when it comes to their flowers. Some have one flower per stalk, some have twelve; some have longer lateral petals; some have slitted labellum; but they all share the same essential features:

- A labellum with a slippery entrance that leads inside, where the insect cannot climb/fly out the way they came in.

- Crawl space leading first towards the stigma and then the pollinia.

- A staminode (sterile stamen) covering the anthers and stigma, which prevents pollinia from being taken by non-pollinators.

- A tight exit pathway lined with hairs where the pollinia are located. This pathway selects for insects of appropriate size.

Pollination of Cypripedium flowers rely on their pollinators to follow a predetermined path from the labellum opening, into the pouch, and out the back exits where the pollinium are glued on. Image on the left is from Li et al, 2012. This image shows C. sichuanense and most importantly, a cross-section of their flowers, as well as pollinium that have been glued onto the back of the dung fly.

In my photos below, you can see the characteristic slipper entrance followed by a bee in the process of having the pollinum transferred to its back.

The process of Cypripedium reproduction begins with these showy flowers attracting a suitable insect to their flowers; in this instance, it’s bees. The bees fall into the labellum and are trapped, with no way out but to climb along the hairs towards the staminode, where the pistil and pollina are. The bee uses the hairs on the lateral petals to pull themselves out of the tight passage where the pollina are. If the bee is of appropriate size, the top of their thorax ribs against the sticky side of the pollinium and it becomes attached. I have personally transferred orchid pollina before, and lemme tell ya, the stickiness is no joke. After the bee does this once, hopefully the bee does it again to a separate plant where the pollina can then rub against the stigma; but, there’s a caveat.

Orchids are deceitful.

Orchids by and far do not offer any nectar reward for pollinators, they just look flashy to their pollinators, and once they’re on the lady slipper ride, they’re strapped in. Not only do they trap insects in their flowers and force them to get plant gametes glued on their backs, the pollinators get nothing in return. This is an interesting strategy, but one that apparently has worked. All the Cypripediums need is one pollinator to get fooled twice on two different flowers from two different plants. But, the final caveat is that the pollinators usually can figure out this ruse, and after 1-2 harrowing experiences with no nectar reward, they avoid Cypripedium flowers, and I can’t blame them.

Hey, thanks for reading and I hope you never get trapped in a giant shoe where gamete packets are glued onto your back.

Citations:

- “Cypripedium.” iNaturalist, http://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=any&subview=map&taxon_id=211065. Accessed 20 May 2023.

- “Cypripedium acaule.” iNaturalist, http://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=any&subview=map&taxon_id=47588. Accessed 20 May 2023.

- “Cypripedium candidum.” iNaturalist, http://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=any&subview=map&taxon_id=55628. Accessed 20 May 2023.

- “Cypripedium parviflorum.” iNaturalist, http://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=any&subview=map&taxon_id=50713. Accessed 20 May 2023.

- “Cypripedium reginae.” iNaturalist, http://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=any&subview=map&taxon_id=51434. Accessed 20 May 2023.

- Li, Peng, et al. “Fly Pollination in Cypripedium: A Case Study of Sympatric C. Sichuanense and C. Micranthum.” Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, vol. 170, no. 1, 2012, pp. 50–58, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.2012.01259.x.

Leave a comment