As it turns out- you can.

Table of Contents:

- Do Plants Talk? (Intro)

- TLDR (Duh)

- How to Train Your Algorithm (Experimental design)

- Let Me Whisper In Your Microphone. Tell Ya Somethin’ That Ya Might Like to Hear. (The good stuff)

- The Future of Plant Communication (Application)

- Citations (Duh)

Do Plants Talk?

As I’m sure you are aware, reader, plants live completely different lives than animals. Sessile creatures with no obvious organs for sensory, how in the world do plants react to stimuli, grow against gravity, know when to reproduce, and topically, how do they communicate with other members of the same species? It isn’t obvious, and scientists have been debating for years whether or not they actually could. Furthermore, if they can, what cockamamie mechanism would plants have that allows for communication? We now know plants communicate in two main ways- Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) and through the mycorrhizal-plant network. In brief, VOCs are chemicals that are released in response to stimuli that confer either resistance to diseases and/or pests within the same plant or other nearby plants, or recruit insects to the plant (another interesting subject, but alas I won’t be covering it here). Classically, VOC communication can be thought of as one plant is being eaten by a fat caterpillar. In response, the plant releases VOCs that alert nearby plants to ramp up anti-herbivory compounds. In contrast, the mycorrhizal-plant network allows plant to plant communication underground through an interconnected highway of fungal hyphae. Signaling compounds are transported across gradients to other nearby plants that alter their responses. Think of waterfalls when you picture chemical gradients- the gradient of water moves from high to low. Its the same concept for chemical concentrations.

Its important to keep in mind throughout these discussions on plant communication not to anthropomorphize our botanical friends, as of the current scientific consensus, plants do not have sapience or sentience and are unable to make thought out plans of helping nearby plant-friends. The intriguing world of plant-communication rests upon a basis of chemical gradients, except, as it turns out, this isn’t the whole picture.

My interest recently has been turned towards a paper posted in the journal Cell, titled “Sounds emitted by plants under stress are airborne and informative,” on March 30, 2023 from Tel-Aviv University, Israel. This landmark study has given light on to something long questioned, but never answered, “do plants emit sounds that convey information; and, can we hear and differentiate them?” As it turns out, we can, and that’s exactly what the researchers have shown. Here, I will break down the fascinating findings of this fresh-off-the-press research.

TLDR

To start, here is the gist: Khait et al wanted to know if plants emitted airborne sounds under different stressful situations, and if those sounds could be identified and differentiated from each other. Furthermore, can other organisms interpret and respond to these airborne sounds (Khait et al, 2023)? To achieve this, the team studied two plants, tobacco and tomato, under two stressed conditions, being cut and drought, in an acoustically isolated box and a more noisy greenhouse. Using a machine learning algorithm, the team was able to classify both the plants and their airborne noises with a 70-98% accuracy (Khait et al, 2023). Pretty phenomenal stuff. If that has gotten your interest, keep reading; you’re gonna love the nitty-gritty.

How to Train Your Algorithm

Specifically, the study has 4 different experimental groups with 3 controls, in two settings, those are, Tomato-cut, Tomato-dry, Tobacco-cut, and Tobacco-dry; and, same-plant prior treatment control, same-species no-treatment neighbor control, and empty pot control; and an acoustic box setting, and a greenhouse setting, respectively. The cut treatment involves healthy plants that are cut above the soil right before recording and the removed stem portion was then recorded. In the drought experiment, healthy plants were allowed to dry out their soil for 4-6 days until the soil moisture content reached below 5%. Each experiment was controlled in the three ways listed above in every recording. Each experimental plant was recorded prior to the stressed condition to self-control. Each experimental plant was recorded with a nearby, healthy, same-species plant for neighbor-control. Finally, they controlled for noises from pots with wet soil but no plants (Khait et al, 2023).

Two directional microphones were utilized per plant, and three plants were recorded at once per experiment- an experimental plant, and an untreated and treated plant for the previously mentioned neighbor-control. The researchers looked at the ultrasonic range of frequencies (20–150 kHz) [side note- humans can hear in the range of 20 Hz to 20 kHz] (Purves, 2001). Once the researchers had the experimental recordings, they used a trained, machine learning algorithm on the different types of emitted noises, such as Tobacco-cut or greenhouse background noise, and then used it to classify the experimental sounds.

The acoustic box setting was utilized to control for outside noises and receive complete, untainted sound recordings of the plants in all experiments. The sound recordings in the acoustic box setting were then utilized for drought experiments in the greenhouse setting which had a multitude of noises from air conditioners to fans. Whew. That was a lot of explanation for how this experiment works, but its necessary to fully appreciate the design, and more importantly, the results.

Let Me Whisper In Your Microphone. Tell Ya Somethin’ That Ya Might Like to Hear.

The results here were elucidating. Clear indication that plants do in fact make airborne noises under stress and we can differentiate them. In the acoustic box setting, Khait et al found that both of the experimental groups- cut and dry– emitted considerably more noises than any of the controls. To highlight the efficacy of the acoustic box setup, Khait et al noted that in over 500 hours of recording, not a single noise was recorded from the positive control, the pot with no plant.

Acoustic-Box Experimental Results

| Tomato-cut | 25.2 ± 3.2 sounds/hour |

| Tomato-dry | 35.4 ± 6.1 sounds/hour |

| Tobacco-cut | 15.2 ± 2.6 sounds/hour |

| Tobacco-dry | 11.0 ± 1.4 sounds/hour |

| Controls | < 1 sounds/hour |

Other than the rate of sounds, the microphones revealed intriguing info on the quality of noises emitted by the plants. The average-peak sound intensity (dBSPL, or decibel sound pressure level) was around 63 dBSPL for all 4 experimental designs, with average-peak frequencies at 49.2-58.5 kHz, which is in the ultrasonic range of frequencies, relative to humans. For a moment, lets focus on the dBSPL results. What does 63 dBSPL actually mean to us?

dBSPL is a way of measuring sound pressure in air, in Decibels, relative to Pascals- a unit of pressure. In this experiment, the dBSPL were measured at a distance of 10cm away from the plants. So, at 10cm away from the plant, if you could hear the emitted frequencies, the sounds would be about as loud as a normal conversation between people. Crazy cool. Although, the researchers did note due to microphone limitations, the recorded intensities were at the lower range of intensity, so the sounds would actually be a bit louder.

Now I know what you’re sitting there thinking, reader: “C’mon, what the everloving fuck did these plants sound like? Talk about burying the lead!” Well, the researchers did not disappoint, and they altered the frequency to our hearable range and compressed the sounds into a shorter segment from the tomato trials:

Following this, the researchers continued past the cool af portion to the actual practical data for future applications. The machine learning algorithms were surprisingly accurate, 70%, in classifying the noises to their appropriate experimental sets (Tomato-Dry vs. Tomato-Cut; Tobacco-Dry vs. Tobacco-Cut; Tomato-Dry vs. Tobacco-Dry; Tomato-Cut vs. Tobacco-Cut). In addition, the system classified the sounds of the plants vs. the noise of the recording system with 98% accuracy (Khait et al, 2023)- again, crazy cool, but wait, there’s more.

That’s right, the greenhouse study. How would this experimental setup work in a setting with a lot less control, and a lot more background noise? Swimmingly. Focusing only on drought stress, the researchers trained the machine learning model on the background noise of the greenhouse and the noises from the tomato-dry results from the acoustic box experiments, which yielded a trained algorithm with 99.7% accuracy. They then took this trained system and juxtaposed it with sounds of tomatoes in the greenhouse. Here, they found they could identify stressed-plants based on the number of sounds per hour, differentiating between drought-stressed and control with 84% accuracy (Khait et al, 2023).

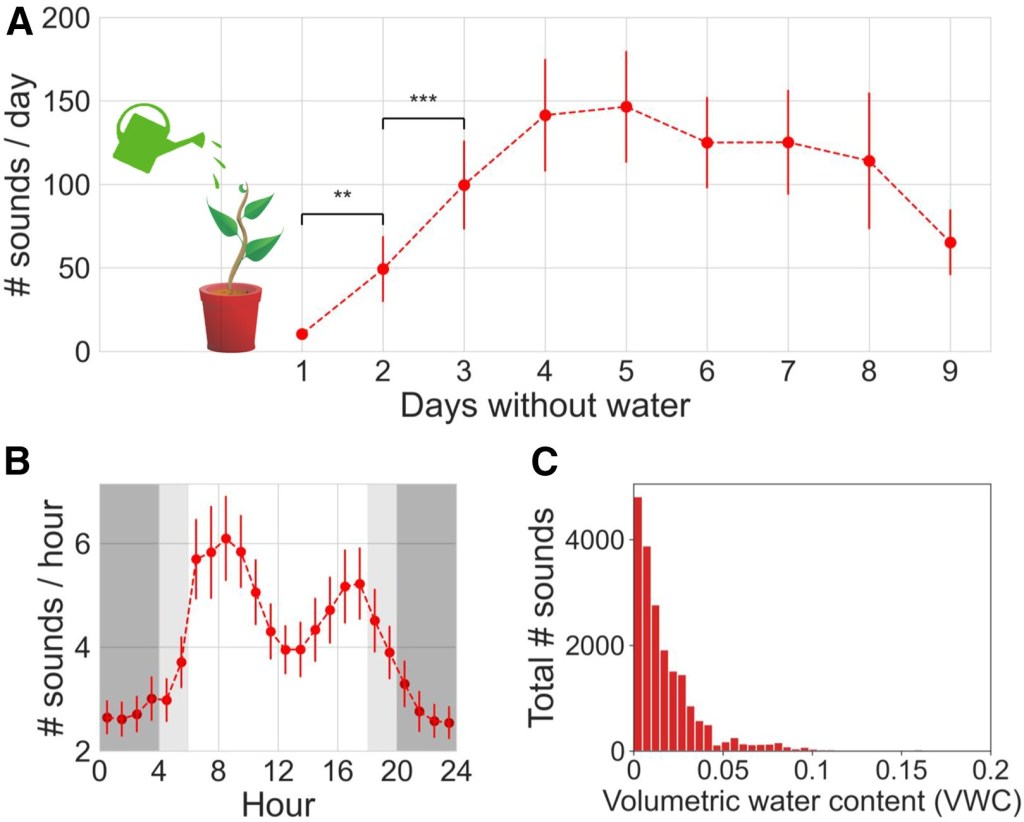

Utilizing this data, the team went further and wanted to know if dehydrating plants emitted sounds in an identifiable pattern over several days. 23 tomato plants were allowed to dehydrate over 9 days. During each recording, the soil’s Volumetric Water Content (VWC) was also measured. VWC is a measurement of volume of water per unit volume of soil and is useful to determine how saturated the soil is. This yielded a pattern of sounds where the plants were fairly quiet while irrigated, made increasingly more sounds 4-5 after irrigation, and then plateaued as they began to dry out (image A below). Furthermore, the sounds emitted by the plants changed based on the time of day, following a bimodal pattern (image B below) which corresponds to when the stomata (plant pores responsible for transpiration) are open during the day. This strongly suggests that the sounds these tomato plants are emitting are linked to the process of transpiration. Using the recorded sounds based upon VWC, the newly trained algorithm could differentiate the sounds of differently dehydrated plants (VWC < 0.05 and VWC > 0.05) with 72% accuracy. Finally, when the number of sounds were measured in comparison to the rate of transpiration, the data revealed an interesting trend: following dehydration, as the rate of transpiration decreased over 5 days, the number of sounds emitted stayed consistent. This suggests that while the noises are correlated to the opening of the stomata, they aren’t necessarily due to the transpirational process (Khait et al, 2023).

As a final note, the researchers took some time to less rigorously look at the sounds of several other plants, which are Triticum aestivum (wheat), Zea mays (corn), Vitis vinifera (Cabernet Sauvignon grapevine), Mammillaria spinosissima (pincushion cactus) and Lamium amplexicaule (henbit). Finally, the sounds of a tomato plant under a different stress, Tobacco Mosaic Virus, were successfully recorded as well (Khait et al, 2023).

The Future of Plant Communication

All of this data and experimental design can boggle the mind, and it can be hard to see the application of the data into the real world. So, how are these plants making sounds, and what’s the value of this?

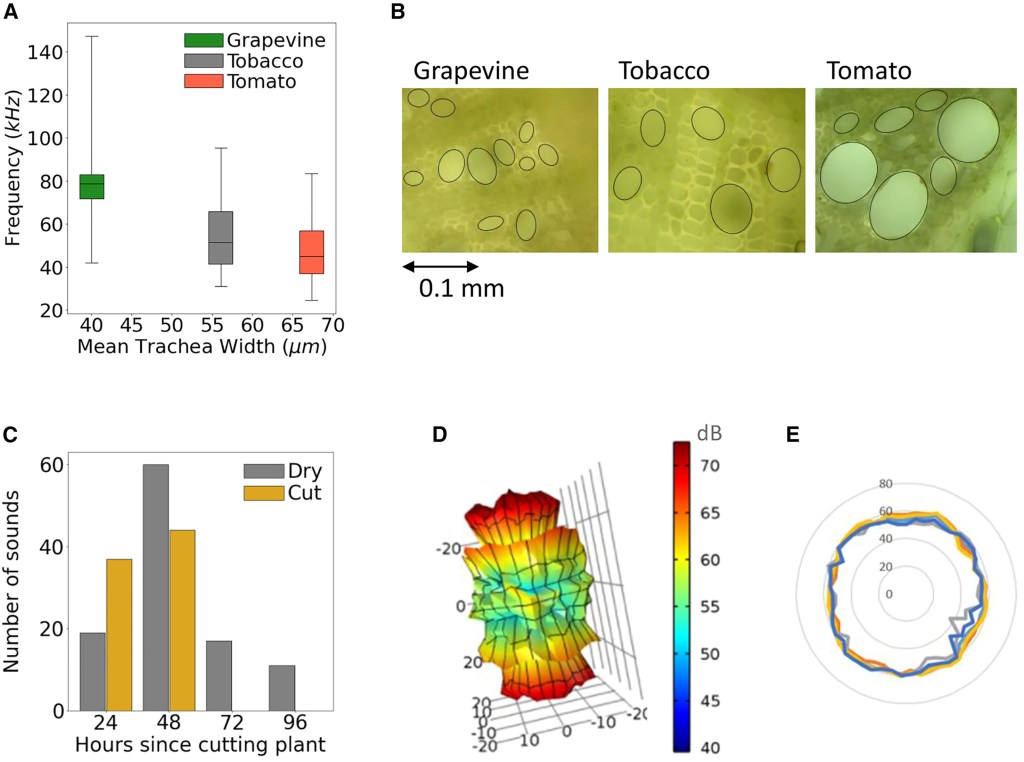

In the discussion section of the study, Khait et al postulate from the data that the sounds being recorded are the result of a process called cavitation, that’s occurring in the trachea (vessels) of the stems. You can think of cavitation as air bubbles forming and popping in a tube. Each time one of these air bubbles pop, a noise is emitted. Tiny tubes mean high frequency sounds. Khait et al back up this hypothesis with several supporting arguments.

- The diameter of the trachea correspond directly to the frequencies of the sounds emitted by different plant species, with wider trachea emitting lower frequencies.

- The patterns of sounds emitted under dehydration follow the gas-physics under the processes of cutting and drought. Where the sounds emitted under cutting spike quickly and taper off, the sounds in drought build then fall over a longer period of time. In addition, the classification of sounds of cut plants were labelled by the algorithm as cut in the first day, and dry in the following days.

- A 3D model developed around the radial projection of sounds based on trachea size is consistent with the ability of the directional mics to pick up the sounds on both sides of the plants.

- The frequencies that cavitating trachea would emit partially overlap with the frequencies recorded in the experiment.

Now that we have a good idea that A. plants emit sounds under stress, B. we can detect these sounds and accurately classify them based on species and stress, even with background noise, and C. we have a working idea of how these plants are making noise, how will this info be applied?

Imagine if you will, a situation in the future where plants are being grown either in a field, or in a greenhouse. There are many different ways plants can be stressed out, and speaking from experience, it isn’t always clear-cut what it is that’s actually causing the stress. A handheld device with an audio receiver and a database of plant sounds could be brought out to the plants to determine exactly what is stressing out your crops. Let’s say, since I live in Ohio, your crop of soybeans is looking no bueno, and you wanna know why. You would only have to select the profile of soybean sounds, take it near your stressed-out crops, and bingo! Your soybeans apparently are infected with a leaf fungus. Or, let’s say you wanna know when to irrigate your crops more efficiently. You could use the same device to listen directly to when your crops are starting to dehydrate. This could revolutionize our process of pest management, irrigation practices, arboriculture, etc.

Secondly, you could take this same principal of identifying specific plant noises and utilizing them to our benefit. Remember in the introductory paragraph where I discussed VOCs and how insects can detect them and know which plants are vulnerable to their attack? We could use plant noises as a non-chemical pesticide. If you have a problem with insects eating your plants, you could set up a loud speaker emitting the stress-response noise of insect herbivory in the frequency range that the insects can detect. This would serve as an attractant to the loud speaker instead of your plants, and it would mean we could spray less pesticides into the environment.

Finally, for conservationists, the identification of plant noises based on species could be extremely useful. If you are determining the species profile of a region, and you already have a database of plant sounds dialed into your region, you could utilize the same handheld device to tell you the species makeup of your surrounding area, based only on the ultrasonic frequencies that we cannot detect. Khait et al in the study even mentioned that the plant sounds could be detected up to 3-5m away by certain insects with sensitive enough detection capabilities. The “sensitive enough” tech we could develop might be expensive, but man oh man would that be useful. We already use this principle to identify hard to spot amphibians and birds for sightings in the field. This would give us an entirely new sense to respond to the environment that we never had before.

I greatly look forward to the future of actually conversing with plants.

Citations:

- Bouwmeester, Harro, et al. “The Role of Volatiles in Plant Communication.” The Plant Journal, vol. 100, no. 5, 2019, pp. 892–907., https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.14496.

- Gorzelak, Monika A., et al. “Inter-Plant Communication through Mycorrhizal Networks Mediates Complex Adaptive Behaviour in Plant Communities.” AoB Plants, vol. 7, 15 May 2015, https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plv050. Accessed 20 Apr. 2023.

- Khait, Itzhak, et al. “Sounds Emitted by Plants under Stress Are Airborne and Informative.” Cell, vol. 186, no. 7, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.03.009. Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

- Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al., editors. Neuroscience. 2nd edition. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2001. The Audible Spectrum. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10924/

Leave a comment