Dedicated to my friend and coworker who asks good questions

By Lily Rice- 1/20/2023

Recently, my coworker, who shall be named ‘But can I eat it,’ has asked me how evolution works and how new traits evolve in a species. To that I said, “Ah dude, that’s like, an entire biology course of information at the bare minimum… tell you what, I’ll make a blog post about it instead!”

To Make Things Confusing

While evolution is perhaps the most well-supported scientific theory, explaining it can be quite tricky. We humans like to put things into neat little boxes that help to explain the messy world to our ill-equipped great-ape brains. The problem is, mother nature doesn’t play nice. Our whole system of taxonomy and phylogeny, while helpful for us to understand relatedness and shared adaptations to environments, are a farcical summarization of true reality. Species are made up, just as the multi-tome rulebooks to Dungeons & Dragons are.

Species are often thought of as living organisms that share similar genes that can only interbreed together. Unfortunately, that’s not always true; species exist as a gradation of physical and genetic characteristics, and sometimes mother nature throws the “Player’s Handbook” out the window, and plants are the optimal case study for how. My last post touched on whole genome duplications (WGDs) and how plants can adapt to harsh environments utilizing these extra genes; but, I left out the part where WGDs can sometimes ‘spontaneously’ create entirely new species that are unable to breed with the parent species. Furthermore, unlike most animals, interbreeding is not limited to the same species, and separate species within the same plant genus, or even plant family can sometimes make offspring capable of reproduction- unlike the classic examples of ligers [lions x tigers] and mules [horse x donkey] who are sterile. Finally, plants are highly plastic organisms that change morphologically to their environments quite well. Two organisms that look nothing alike can be quite closely related, a feature of plants that stymies old & new botanists alike. On that last point, let me give you an example:

In mammals, the order Carnivora contains animals like bears, cats, wolves, and raccoons. It’s not hard to see they are more closely related to each other than a pangolin in the order Pholidota. Now let’s look at two species of plants: Lobelia siphilitica & Tanacetum bipinnatum– Blue Lobelia & Dune Tansy respectively. It’s much harder to believe that these two are related by the plant order Asterales. In my opinion, the physical similarities are lacking. As a novice botanist, with no context, I would have an easier time believing L. siphilitica was more closely related to the two Lamiales members below than the Dune Tansy.

To Make Things Clear

Now that I’ve added some uncertainty to plant evolution, let me clear things up.

While plants break the evolutionary rules that are typical to animal groups, they are not unusual for the life histories and anatomy of plants when you think about it.

Plants live entirely different lives than animals do. Plants are unmoving organisms that receive their energy from the sun, through chloroplasts, which are spread through most of their above ground body. Imagine if you will: your body but with thousands of tiny mouths from the waist up, terrifying right? Plants have no ways to communicate other than chemicals passed along gradients. Plants require other forces to reproduce for them, like bats, bees, and wind; and occasionally will reproduce with just themselves, or, they will clone themselves through various crazy methods. Plants can lose entire “limbs” without much of a care and simply grow new ones.

I could go on and on. But the point is: think of the ways plant lives differ from animal lives.

- How do plants obtain energy?

- How do plants get water & nutrients?

- How do plants defend & protect themselves?

- How do plants reproduce?

- How do plants communicate with organisms of the same species?

- How does being sessile change the way plants perform the previous questions?

There are many ways plants have answered these questions. Each answer is a different way plants have evolved over millions of years to be adapted to the environments they live in.

To Answer the Question

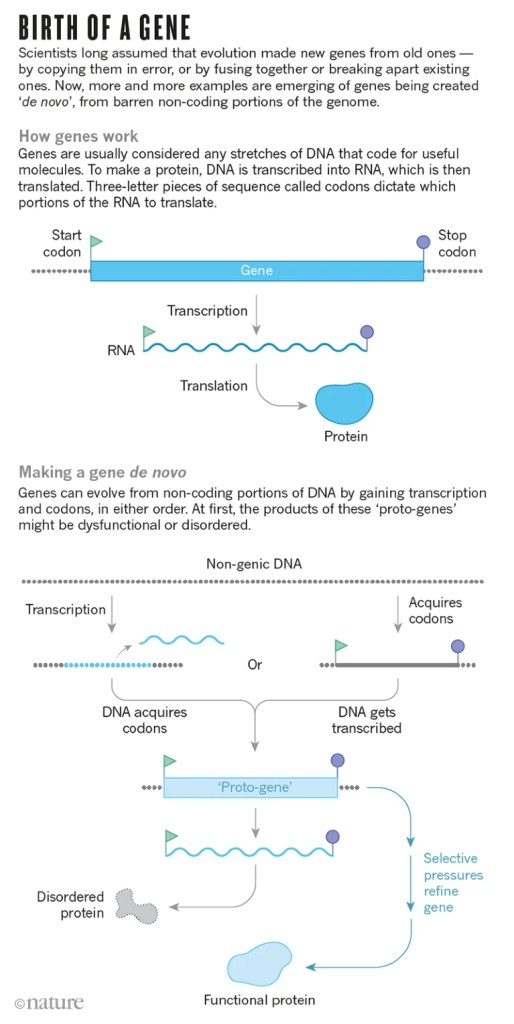

Evolution works on the heritable parts of a species, namely genes, which are the codes of DNA that act as blueprints for our bodies. Four letters: A, C, T, & G (Adenine, Cytosine, Thymine, & Guanine respectively). These letters work as the scripts for which cellular machinery prints out RNA, which then prints out proteins, which in turn make up almost everything that living organisms are made of. Alterations to any step in the process may drastically alter the gene products. As long as the alterations are tied to genetic code, evolution can work on it. Alternative forms of genes are known as alleles, and those form the variation of traits that we see- a classic example for alleles are Mendel’s pea colors. Different alleles make pink or white peas.

Simply put, evolution works on the change of the frequency of alleles between generations. Imagine you have a population of 100 Mendel’s peas; 20 have the white peas, 80 have the pink peas. In this situation, the white peas offer some sort of reproductive benefit, so they are able to make more seeds. Next generation we have 40 white peas and 60 pink peas. That’s evolution (in the small scale).

There are currently 5 mechanisms of evolution that affect allele frequencies:

- Mutation

- Gene flow (migration)

- Genetic drift (random population change)

- Non-random mating

- Natural selection

It only takes one of these mechanisms to cause a gene to evolve, for now I’m only going to focus on the first two mechanisms. Mr. ‘But can I eat it,’ it’s finally time to answer how new traits (genes) evolve in a species.

Mutation & gene flow are the two main ways new genes come into a population, with a caveat- they come from already pre-existing genes. Gene flow, or migration, can bring genes that don’t exist in one population from another. Suddenly, this population has a new gene. Mutations on the other hand, have the unique ability of altering existing genes.

Mutations can happen in many different ways. From an error in transcription or translation replacing/deleting/adding bases of DNA/RNA, to a virus incorporating foreign DNA/RNA into the host’s genome. Mutations are the main way existing genes are altered in a population. A simple change of one base pair can change an amino acid which can cause the resulting protein to fold differently, and therefore have a different function. Most of the mutations that happen in your DNA is A) not in sex cells so therefore cannot be passed on, and B) either ineffective or outright bad. The few mutations that go against the grain can be selected on and improved upon. Beneficial mutations aren’t terribly hard to find examples of in the plant world, since WGD’s are a type of mutation, and they are incredibly common in the plant world.

There’s a lot of discussion about how existing genes evolve and alter species, but the question often comes back to “where do new genes come from?” For the longest time, de novo (new) genes were lauded as a hoax- but as our understanding of DNA has expanded, so has our understanding of genetic evolution. The 2 main modes of thought when it comes to de novo genes are Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) and what I’ll call ‘Junk-DNA Beta-Testing.’

Horizontal Gene Transfer is an interesting concept. Unlike Vertical Gene Transfer- where genetic material is passed into offspring from the parents- in HGT, a species can get “alien” genetic code, which can come from other organisms or different species. The mechanism of HGT is kinda complicated, and I need not bore you with the details, but the idea is a section of foreign DNA is inserted into the DNA of the host, and potentially the sex cells (which is how the genes are passed on). HGT is much more common amongst prokaryotic microbes (think your traditional bacteria) than eukaryotes (think us or algae). That is not to say it doesn’t happen though, as we have many examples of HGT in eukaryotes.

The classical example of HGT in plants involves a bacteria called Agrobacterium, which infects tobacco and sweet potato plants. The HGT in this example involves the transfer of genes from Agrobacterium into the DNA of tobacco and sweet potato plants which causes tumor growth in plant tissues (Quispe-Huamanquispe & Kreuze, 2015). This example doesn’t result in a beneficial trait for the plants- sometimes that’s how the genetic cookie crumbles. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ But it doesn’t always turn out that way. From the same 2015 paper, they highlight a beneficial HGT example. Most ferns, despite being an ancient lineage of land plants, have diversified quite recently into their modern groups. Part of their success as woodland understory plants is owed to Hornworts, a group of land plants that diverged before ferns did. Through genetic analysis, it was found that a HGT gave ferns a new photoreceptor from Hornworts around 179 million years ago, which enabled ferns to have a more efficient response to light. How that happened is anyone’s guess, but I’m going to buy my nickel down on a virus.

Before I move on to the most exciting research, I should note that human DNA contains approximately 8% viral DNA, some of which when removed from our DNA causes our cells to have a less vigorous response to viral infection, wild (Brouillette, 2016)!

Junk DNA Beta-Testing, what a tantalizing phrase. Also, what Mr. ‘But Can I Eat It’ asked me about- how do species develop new genes?

For the longest time, and throughout my entire undergraduate education, we thought DNA consisted of mostly non-coding “junk” DNA, and very few genes that actually got produced by the cells. There were a lot of hypotheses about why this weight towards “junk” was consistent in DNA, the main idea that was thrown around in my undergrad days was the “junk” DNA acted as a buffer for random mutations; i.e. you’re more likely to conserve your important genes since statistically it’s more likely to have a mutation in the numerous “junk” portions. All in all, these hypotheses still probably hold some water, but scientists began to think this all seemed a bit fishy. Why would you reserve the majority of your genome for non-coding DNA when coding is the whole point of DNA? In fact, the more scientists looked into this “junk” portion, the more they found genetic code that looked like it could be produced by the cell, but wasn’t. So what’s happening here?

That’s the absolute beauty about the scientific process; starting with basic information, we begin to tease apart the true nature of reality bit by bit, developing models and redeveloping models when we get more accurate data.

As it turns out, that “junk” DNA might not be junk after all. Recent research into the “junk” portion has found an interesting concept: the “junk” DNA may serve as a reservoir for genetic experimentation- like Dr. Frankenstein stitching together body parts hoping that the end result works.

The “junk” DNA can sometimes gain the ability to be transcribed into RNA and then translated into a protein, which may be a jumbled unusable mess. But, again like the mad Dr. Frankenstein, the process gets tweaked again and again until the new protein is something functional. In response to a new environmental stimulus, you can see how this would be useful. If your species doesn’t have the genetic tools to deal with this new hurdle, give it time and the whole species can beta-test different “proto-genes” until you finally have a working solution. This new understanding helps to explain how evolution can work in ‘great leaps’ instead of the usual slow march.

In the article, “How Evolution Builds Genes from Scratch,” the author, Levy, details research into antifreeze proteins in Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua). The researchers were looking into the evolutionary origin of this trait and expected to find a similar antifreeze gene in G. morhua’s closest relatives, but to their surprise, none was found. After some very sciency and nerdy sleuthing, the researchers found mentions of genes being built from scratch in other papers. When they looked back at the genome of G. morhua, the pieces slid into place that this gene was freshly minted, (or de novo in nerdese). According to this research, in response to a cooling climate, G. morhua acquired this antifreeze gene 15 million years ago.

More and more as we look into DNA, we are finding de novo genes popping up everywhere. 15 shared across the primate order, 60 in humans, 175 in a strain of rice, and at least one really badass gene in Atlantic Cod (Levy, 2019). As science continues its steady march, the intricate process of beta-testing de novo genes will become clearer and clearer, and our understanding of how species evolve will become that much clearer.

Citations:

- Brouillette, Monique. “Viral ‘Fossils’ in Our DNA May Help Us Fight Infection.” Science, 3 Mar. 2016, https://www.science.org/content/article/vviral-fossils-our-dna-may-help-us-fight-infection

- Levy, Adam. “How Evolution Builds Genes from Scratch.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 16 Oct. 2019, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-03061-x#:~:text=Each%20new%20gene%20must%20have,each%20with%20their%20own%20function.

- Quispe-Huamanquispe DG, Gheysen G and Kreuze JF (2017) Horizontal Gene Transfer Contributes to Plant Evolution: The Case of Agrobacterium T-DNAs. Front. Plant Sci. 8:2015. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.02015

Leave a comment